The pattern is now familiar. I received another anonymous review by Reviewer 2 from a z-curve article that repeated Pek’s concerns about the performance of z-curve. To deal with biased reviewers, journals allow authors to mention potentially biased reviewers. I suggest doing so for Pek. I also suggest sharing a manuscript with me to ensure proper interpretation of results and to make it “reviewer-safe.”

To justify the claim that Pek is biased, researchers can use this rebuttal of Pek’s unscientific claims about z-curve.

Reviewer 2 (either Pek or a Pek parrot)

Reviewer Report:

The manuscript “A review and z-curve analysis of research on the palliative association of system justification” (Manuscript ID 1598066) extends the work of Sotola and Credé (2022), who used Z-curve analysis to evaluate the evidential value of findings related to system justification theory (SJT). The present paper similarly reports estimates of publication bias, questionable research practices (QRPs), and replication rates in the SJT literature using Z-curve. Evaluating how scientific evidence accumulates in the published literature is unquestionably important.

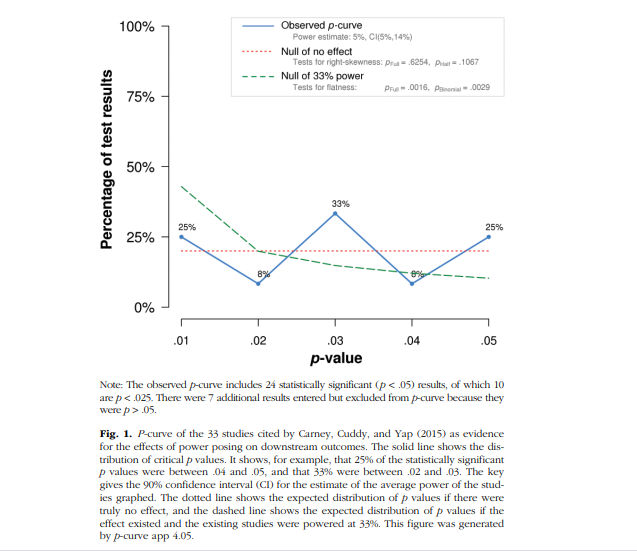

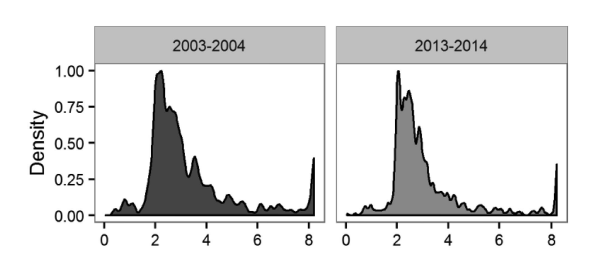

However, there is growing concern about the performance of meta-analytic forensic tools such as p-curve (Simonsohn, Nelson, & Simmons, 2014; see Morey & Davis-Stober, 2025 for a critique) and Z-curve (Brunner & Schimmack, 2020; Bartoš & Schimmack, 2022; see Pek et al., in press for a critique). Independent simulation studies increasingly suggest that these methods may perform poorly under realistic conditions, potentially yielding misleading results.

Justification for a theory or method typically requires subjecting it to a severe test (Mayo, 2019) – that is, assuming the opposite of what one seeks to establish (e.g., a null hypothesis of no effect) and demonstrating that this assumption leads to contradiction. In contrast, the simulation work used to support Z-curve (Brunner & Schimmack, 2020; Bartoš & Schimmack, 2022) relies on affirming belief through confirmation, a well-documented cognitive bias.

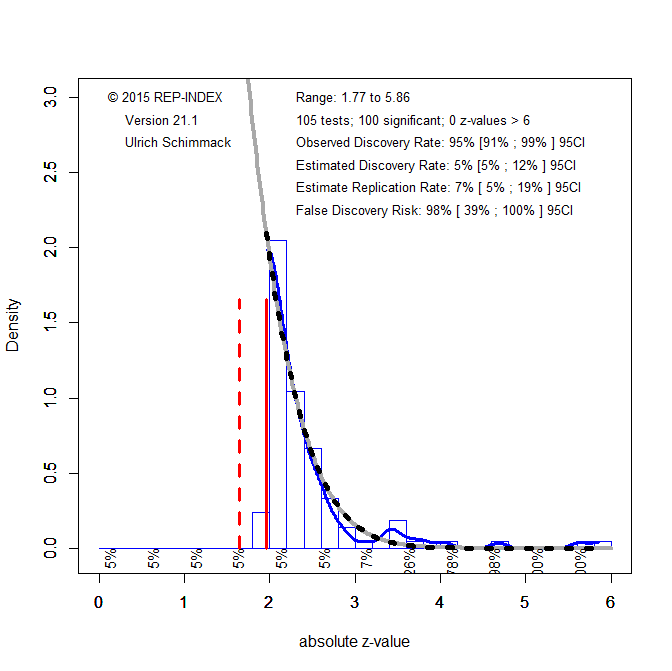

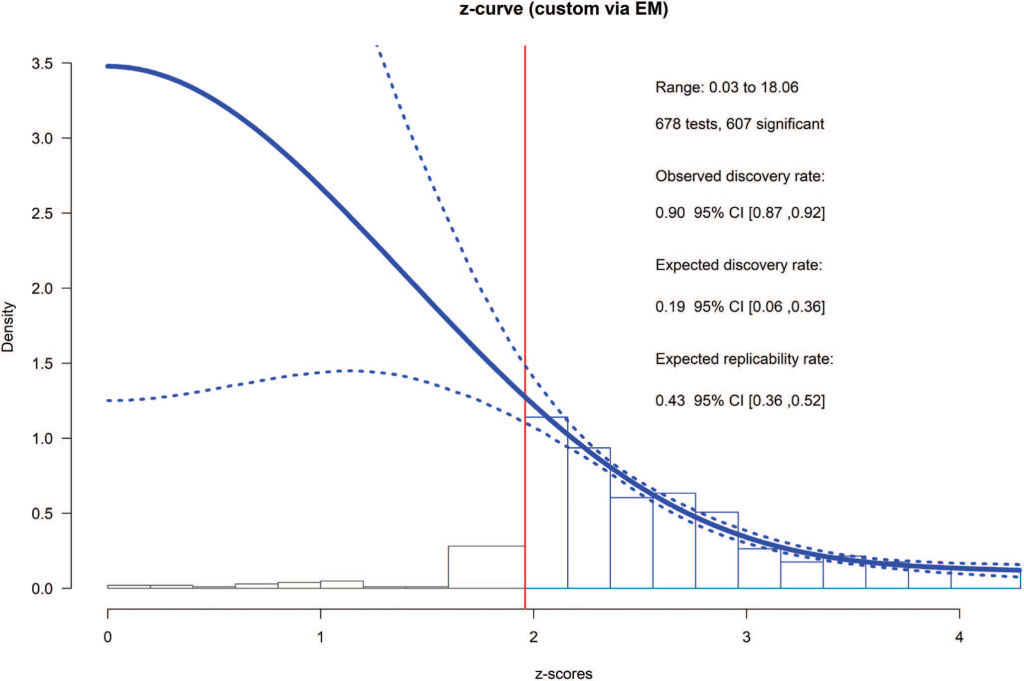

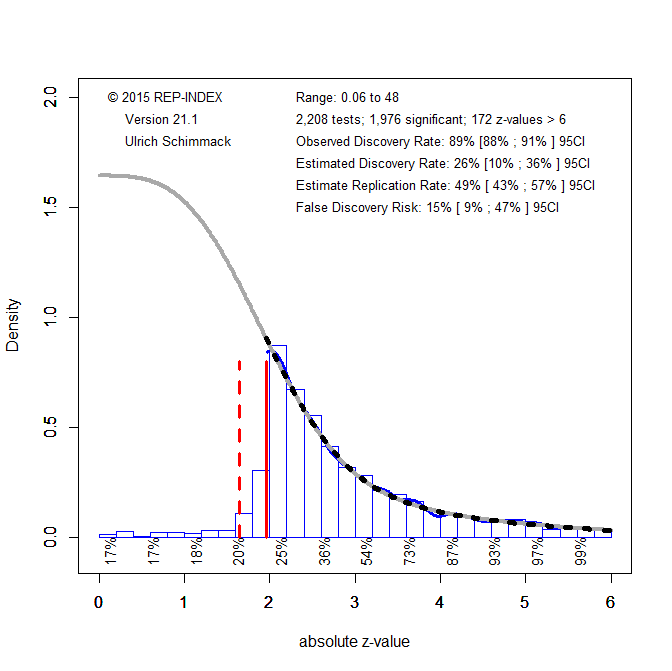

Findings from Pek et al. (in press) show that when selection bias is presented in published p-values — the very scenario Z-curve was intended to be applied — estimates of the expected discovery rate (EDR), expected replication rate (ERR), and Sorić’s False Discovery Risk (FDR) are themselves biased.

The magnitude and direction of this bias depend on multiple factors (e.g., number of p-values, selection mechanism of p-values) and cannot be corrected or detected from empirical data alone. The manuscript’s main contribution rests on the assumption that Z-curve yields reasonable estimates of the “reliability of published studies,” operationalized as a high ERR, and that the difference between the observed discovery rate (ODR) and EDR quantifies the extent of QRPs and publication bias.

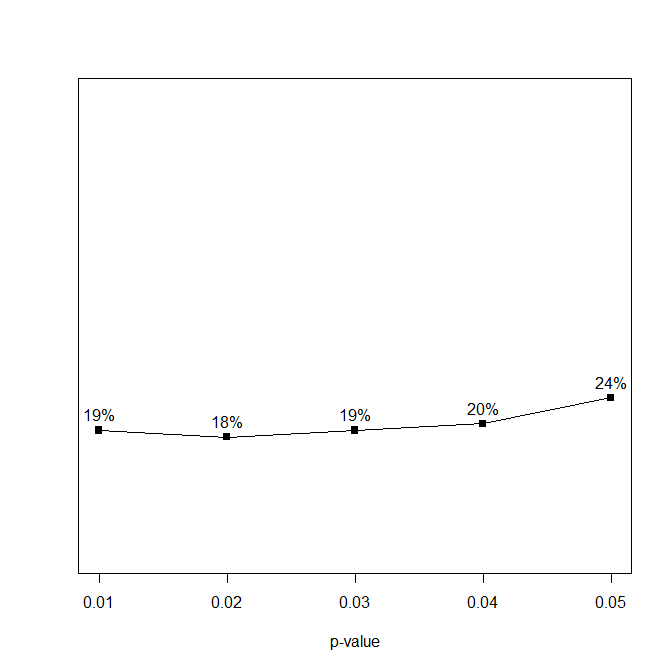

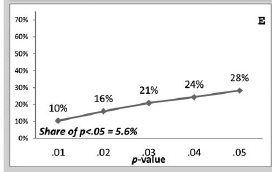

The paper reports an ERR of .76, 95% CI [.53, .91] and concludes that research on the palliative hypothesis may be more reliable than findings in many other areas of psychology. There are several issues with this claim. First, the assertion that Sotola (2023) validated ERR estimates from the Z-curve reflects confirmation bias – I have not read Röseler (2023) and cannot comment on the argument made in it. The argument rests solely on the descriptive similarly between the ERR produced by Z-curve and the replication rate reported by the Open Science Collaboration (2015). However, no formal test of equivalence was conducted, and no consideration was given to estimate imprecision, potential bias in the estimates, or the conditions under which such agreement might occur by chance.

At minimum, if Z-curve estimates are treated as predicted values, some form of cross-validation or prediction interval should be used to quantify prediction uncertainty. More broadly, because ERR estimates produced by Z-curve are themselves likely biased (as shown in Pek et al., in press), and because the magnitude and direction of this bias are unknown, comparisons about ERR values across literatures do not provide a strong evidential basis for claims about the relative reliability of research areas.

Furthermore, the width of the 95% CI spans roughly half of the bounded parameter space of [0, 1], indicating substantial imprecision. Any claims based on these estimates should thus be contextualized with appropriate caution.

Another key result concerns the comparison of EDR = .52, 95% CO [.14, .92], and ODR = .81, 95% CI = [.69, .90]. The manuscript states that “When these two estimates are highly discrepant, this is consistent with the presence of questionable research practices (QRPS) and publication bias in this area of research (Brunner & Schimmack, 2020).

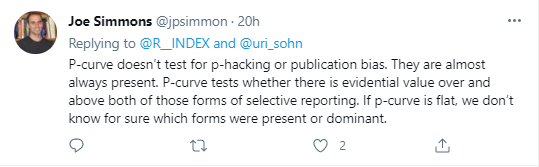

But in this case, the 95% CIs for the EDR and ODR in this work overlapped quite a bit, meaning that they may not be significantly different…” (p. 22). There are several issues with such a claim. First, Z curve results cannot directly support claims about the presence of QRPs.

The EDR reflects the proportion of significant p values expected under no selection bias, but it does not identify the source of selection bias (e.g., QRPs, fraud, editorial decisions). Using Z curve requires accepting its assumed missing data mechanism—a strong assumption that cannot be empirically validated.

Second, a descriptive comparison between two estimates cannot be interpreted as a formal test of difference (e.g., eyeballing two estimates of means as different does not tell us whether this difference is not driven by sampling variability). Means can be significantly different even if their confidence intervals overlap (Cumming & Finch, 2005).

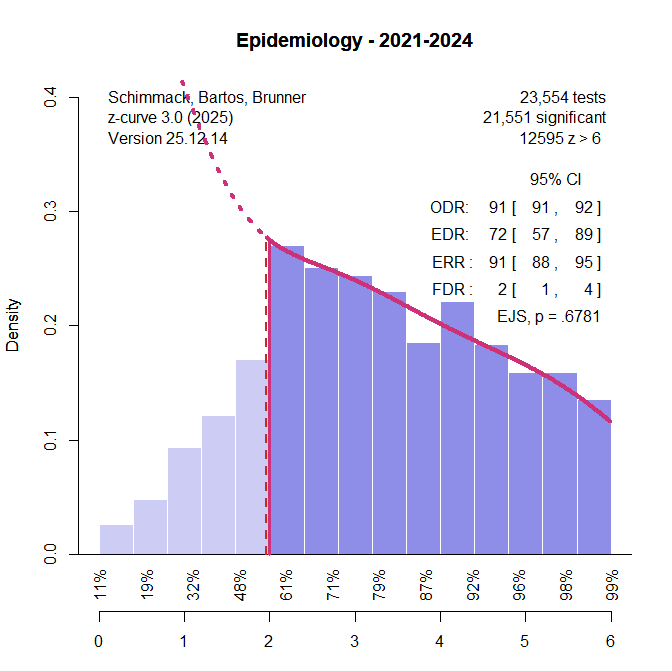

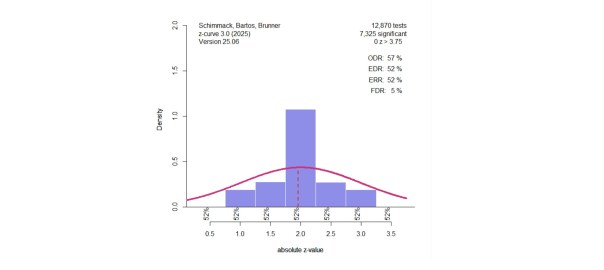

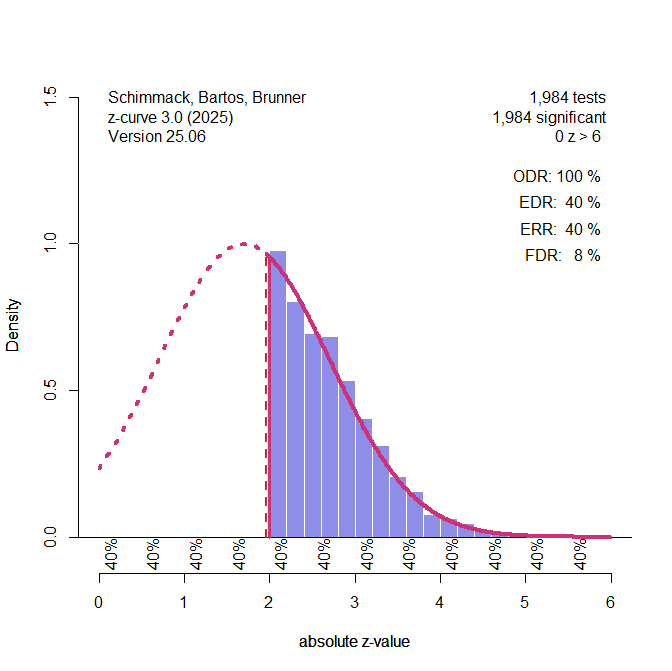

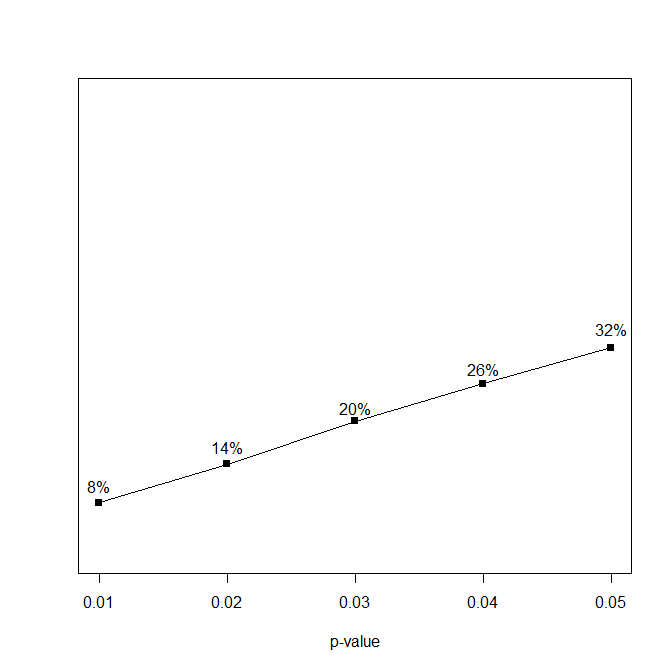

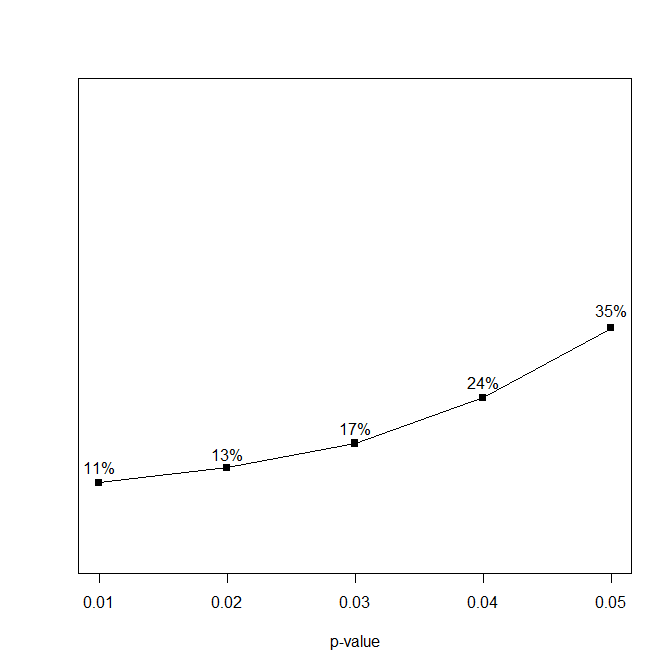

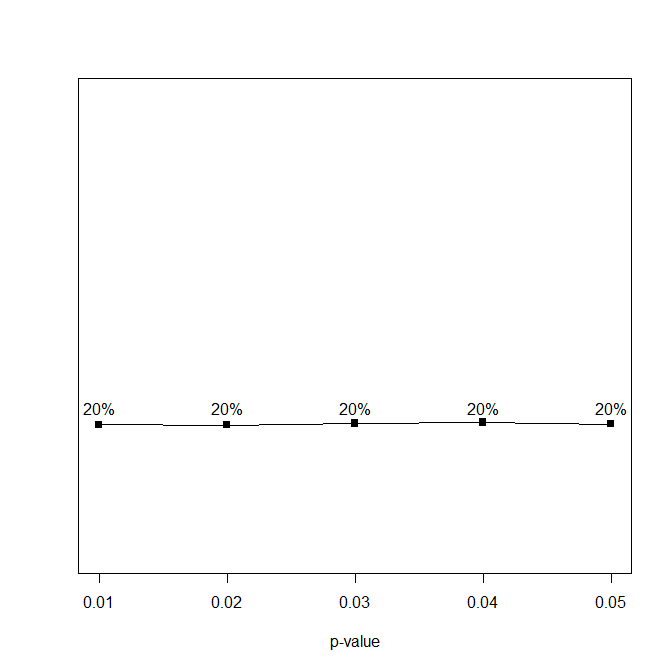

A formal test of the difference is required. Third, EDR estimates can be biased. Even under ideal conditions, convergence to the population values requires extremely large numbers of studies (e.g., > 3000, see Figure 1 of Pek et al., in press).

The current study only has 64 tests. Thus, even if a formal test of the difference of ODR – EDR was conducted, little confidence could be placed on the result if the EDR estimate is biased and does not reflect the true population value.

Although I am critical of the outputs of Z curve analysis due to its poor statistical performance under realistic conditions, the manuscript has several strengths. These include adherence to good meta analytic practices such as providing a PRISMA flow chart, clearly stating inclusion and exclusion criteria, and verifying the calculation of p values. These aspects could be further strengthened by reporting test–retest reliability (given that a single author coded all studies) and by explicitly defining the population of selected p values. Because there appears to be heterogeneity in the results, a random effects meta analysis may be appropriate, and study level variables (e.g., type of hypothesis or analysis) could be used to explain between study variability. Additionally, the independence of p values has not been clearly addressed; p values may be correlated within articles or across studies. Minor points: The “reliability” of studies should be explicitly defined. The work by Manapat et al. (2022) should be cited in relation to Nagy et al. (2025). The findings of Simmons et al. (2011) applies only to single studies.

However, most research is published in multi-study sets, and follow-up simulations by Wegener at al. (2024) indicate that the Type I error rate is well-controlled when methodological constraints (e.g., same test, same design, same measures) are applied consistently across multiple studies – thus, the concerns of Simmons et al. (2011) pertain to a very small number of published results.

I could not find the reference to Schimmack and Brunner (2023) cited on p. 17.

Rebuttal to Core Claims in Recent Critiques of z-Curve

1. Claim: z-curve “performs poorly under realistic conditions”

Rebuttal

The claim that z-curve “performs poorly under realistic conditions” is not supported by the full body of available evidence. While recent critiques demonstrate that z-curve estimates—particularly EDR—can be biased under specific data-generating and selection mechanisms, these findings do not justify a general conclusion of poor performance.

Z-curve has been evaluated in extensive simulation studies that examined a wide range of empirically plausible scenarios, including heterogeneous power distributions, mixtures of low- and high-powered studies, varying false-positive rates, different degrees of selection for significance, and multiple shapes of observed z-value distributions (e.g., unimodal, right-skewed, and multimodal distributions). These simulations explicitly included sample sizes as low as k ≈ 100, which is typical for applied meta-research in psychology.

Across these conditions, z-curve demonstrated reasonable statistical properties conditional on its assumptions, including interpretable ERR and EDR estimates and confidence intervals with acceptable coverage in most realistic regimes. Importantly, these studies also identified conditions under which estimation becomes less informative—such as when the observed z-value distribution provides little information about missing nonsignificant results—thereby documenting diagnosable scope limits rather than undifferentiated poor performance.

Recent critiques rely primarily on selective adversarial scenarios and extrapolate from these to broad claims about “realistic conditions,” while not engaging with the earlier simulation literature that systematically evaluated z-curve across a much broader parameter space. A balanced scientific assessment therefore supports a more limited conclusion: z-curve has identifiable limitations and scope conditions, but existing simulation evidence does not support the claim that it generally performs poorly under realistic conditions.

2. Claim: Bias in EDR or ERR renders these estimates uninterpretable or misleading

Rebuttal

The critique conflates the possibility of bias with a lack of inferential value. All methods used to evaluate published literatures under selection—including effect-size meta-analysis, selection models, and Bayesian hierarchical approaches—are biased under some violations of their assumptions. The existence of bias therefore does not imply that an estimator is uninformative.

Z-curve explicitly reports uncertainty through bootstrap confidence intervals, which quantify sampling variability and model uncertainty given the observed data. No evidence is presented that z-curve confidence intervals systematically fail to achieve nominal coverage under conditions relevant to applied analyses. The appropriate conclusion is that z-curve estimates must be interpreted conditionally and cautiously, not that they lack statistical meaning.

3. Claim: Reliable EDR estimation requires “extremely large” numbers of studies (e.g., >3000)

Rebuttal

This claim overgeneralizes results from specific, highly constrained simulation scenarios. The cited sample sizes correspond to conditions in which the observed data provide little identifying information, not to a general requirement for statistical validity.

In applied statistics, consistency in the limit does not imply that estimates at smaller sample sizes are meaningless; it implies that uncertainty must be acknowledged. In the present application, this uncertainty is explicitly reflected in wide confidence intervals. Small sample sizes therefore affect precision, not validity, and do not justify dismissing the estimates outright.

4. Claim: Differences between ODR and EDR cannot support inferences about selection or questionable research practices

Rebuttal

It is correct that differences between ODR and EDR do not identify the source of selection (e.g., QRPs, editorial decisions, or other mechanisms). However, the critique goes further by implying that such differences lack diagnostic value altogether.

Under the z-curve framework, ODR–EDR discrepancies are interpreted as evidence of selection, not of specific researcher behaviors. This inference is explicitly conditional and does not rely on attributing intent or mechanism. Rejecting this interpretation would require demonstrating that ODR–EDR differences are uninformative even under monotonic selection on statistical significance, which has not been shown.

5. Claim: ERR comparisons across literatures lack evidential basis because bias direction is unknown

Rebuttal

The critique asserts that because ERR estimates may be biased with unknown direction, comparisons across literatures lack evidential value. This conclusion does not follow.

Bias does not eliminate comparative information unless it is shown to be large, variable, and systematically distorting rankings across plausible conditions. No evidence is provided that ERR estimates reverse ordering across literatures or are less informative than alternative metrics. While comparative claims should be interpreted cautiously, caution does not imply the absence of evidential content.

6. Claim: z-curve validation relies on “affirming belief through confirmation”

Rebuttal

This characterization misrepresents the role of simulation studies in statistical methodology. Simulation-based evaluation of estimators under known data-generating processes is the standard approach for assessing bias, variance, and coverage across frequentist and Bayesian methods alike.

Characterizing simulation-based validation as epistemically deficient would apply equally to conventional meta-analysis, selection models, and hierarchical Bayesian approaches. No alternative validation framework is proposed that would avoid reliance on model-based simulation.

7. Implicit claim: Effect-size meta-analysis provides a firmer basis for credibility assessment

Rebuttal

Effect-size meta-analysis addresses a different inferential target. It presupposes that studies estimate commensurable effects of a common hypothesis. In heterogeneous literatures, pooled effect sizes represent averages over substantively distinct estimands and may lack clear interpretation.

Moreover, effect-size meta-analysis does not estimate discovery rates, replication probabilities, or false-positive risk, nor does it model selection unless explicitly extended. No evidence is provided that effect-size meta-analysis offers superior performance for evaluating evidential credibility under selective reporting.

Summary

The critiques correctly identify that z-curve is a model-based method with assumptions and scope conditions. However, they systematically extend these points beyond what the evidence supports by:

- extrapolating from selective adversarial simulations,

- conflating potential bias with lack of inferential value,

- overgeneralizing small-sample limitations,

- and applying asymmetrical standards relative to conventional methods.

A scientifically justified conclusion is that z-curve provides conditionally informative estimates with quantifiable uncertainty, not that it lacks statistical validity or evidential relevance.