Authors: Maria Soto and Ulrich Schimmack

Citation: Soto, M. & Schimmack, U. (2024, July 4/08/13). 2024 Replicability Report for the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. Replicability Index.

https://replicationindex.com/2024/07/04/rr24-jesp/Introduction

In the 2010s, it became apparent that empirical psychology had a replication problem. When psychologists tested the replicability of 100 results, they found that only 36% of the 97 significant results in original studies could be reproduced (Open Science Collaboration, 2015). In addition, several prominent cases of research fraud further undermined trust in published results. Over the past decade, several proposals were made to improve the credibility of psychology as a science. Replicability Reports aim to improve the credibility of psychological science by examining the amount of publication bias and the strength of evidence for empirical claims in psychology journals.

The main problem in psychological science is the selective publishing of statistically significant results and the blind trust in statistically significant results as evidence for researchers’ theoretical claims. Unfortunately, psychologists have been unable to self-regulate their behaviour and continue to use unscientific practices to hide evidence that disconfirms their predictions. Moreover, ethical researchers who do not use unscientific practices are at a disadvantage in a game that rewards publishing many articles without concern about these findings’ replicability. Replicability reports aim to reward journals that publish credible results and use open science practices that encourage honest reporting of results like preregistration or registered reports.

My colleagues and I have developed a statistical tools that can reveal the use of unscientific practices and predict the outcome of replication studies (Brunner & Schimmack, 2021; Bartos & Schimmack, 2022). This method is called z-curve. Z-curve cannot be used to evaluate the credibility of a single study. However, it can provide valuable information about the research practices in a particular research domain. Replicability-Reports (RR) analyze the statistical results reported in a journal with z-curve to estimate the replicability of published results, the amount of publication bias, and the risk that significant results are false positive results (i.e, the sign of a mean difference or correlation of a significant result does not match the sign in the population).

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

The Journal of Experimental Social Psychology (JESP) was established in 1965. It is the oldest journal that specializes on experimental studies of social cognitions and behaviors. A replicability analysis of this journal is particularly interesting for several reasons. First, the long history of the journal makes it possible to examine historic trends in research practices in this field over a long time period. Second, experimental social psychology has triggered the crisis of confidence in psychological science with studies on extrasensory perception (Bem, 2011), implicit priming (Bargh et al., 1996), and ego depletion (Baumeister et al., 1996) that failed to replicate. At the same time, social psychology has responded to these replication failures by increasing sample sizes and rewarding open science practices like preregistration of analyses plans that limit researchers’ degrees of freedom to fish for significance or change hypotheses after examining the data.

On average, JESP publishes about 150 articles in 6 annual issues. According to Web of Science, the impact factor of JESP ranks 15th in the Psychology, Social category (Clarivate, 2024). The journal has an H-Index of 196 (i.e., 196 articles have received 196 or more citations).

In its lifetime, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology (JESP) has published over 4,200 articles with an average citation rate of 56.01 citations. So far, the journal has published 10 articles with more than 1,000 citations. Most of these have been published before the 2000s. The three most cited articles in the 2000s focus on improving methods used in social psychology research (Oppenheimer et al., 2009; Leys et al., 2013; Peer et al., 2017).

The Open Science Collaboration observed how only 14 out of 55 (25%) social psychology effects were replicated. A similar replicability estimate of 16% to 44% was measured for social psychology by Bartoš & Schimmack (2022). In response, many journals have implemented multiple strategies to improve the replicability and credibility of their published findings. Similarly, JESP introduced the “JESP’s 10-Item Submission Checklist” in 2022. The list entails a series of requirements that authors must fulfill to have their manuscripts reviewed. This checklist requires that authors provide their priori power analysis, sample size determination, and full reporting of all statistics including non-significant ones, among other items that aim to improve the quality of the submitted manuscripts. JESP’s focus on social psychology allows this report to highlight whether the proposed strategies to reform social psychology research meet their expectations.

The current Editor-in-Chief is Professor Nicholas Rule. Professor Kristin Laurin serves as the Senior Associate Editor. The associate editors are Professor Rachel Barkan, Professor Pamela K Smith, Professor Fiona Barlow, Professor Paul Conway, Professor Jarret Crawford, Professor Sarah Gaither, Professor Shlomo Hareli, Professor Edward Hirt, Professor Rachael Jack, Professor Joris Lammers, Professor Pranjal H. Mehta, Professor Kristin Pauker, Professor Brett Peters, Professor Evava Pietr, and Professor Karina Schumann.

Extraction Method

Replication reports are based on automatically extracted test statistics such as F-tests, t-tests, z-tests, and chi2-tests. Additionally, we extracted 95% confidence intervals of odds ratios and regression coefficients. The test statistics were extracted from collected PDF files using a custom R-code. The code relies on the pdftools R package (Ooms, 2024) to render all textboxes from a PDF file into character strings. Once converted the code proceeds to systematically extract the test statistics of interest (Soto & Schimmack, 2024). PDF files identified as editorials, review papers and meta-analyses were excluded. Meta-analyses were excluded to avoid the inclusion of test statistics that were not originally published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. Following extraction, the test statistics are converted into absolute z-scores.

Results For All Years

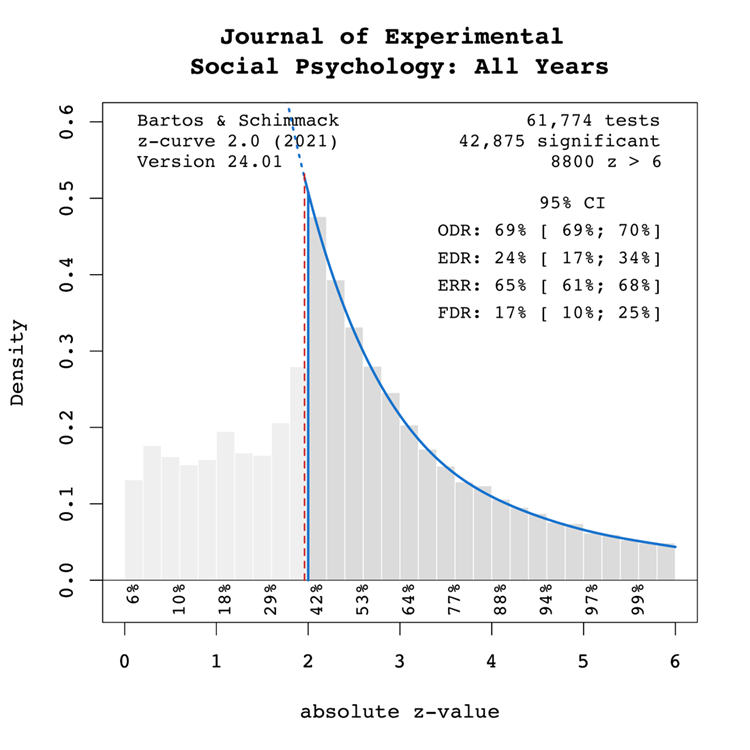

Figure 1 shows a z-curve plot for all articles from 2000-2023 (see Schimmack, 2023, for a detailed description of z-curve plots). The plot is essentially a histogram of all test statistics converted into absolute z-scores (i.e., the direction of an effect is ignored). Z-scores can be interpreted as the strength of evidence against the null hypothesis that there is no statistical relationship between two variables (i.e., the effect size is zero and the expected z-score is zero). A z-curve plot shows the standard criterion of statistical significance (alpha = .05, z = 1.96) as a vertical red dotted line.

Z-curve plots are limited to values less than z = 6. The reason is that values greater than 6 are so extreme that a successful replication is all but certain unless the value is a computational error or based on fraudulent data. The extreme values are still used for the computation of z-curve statistics but omitted from the plot to highlight the shape of the distribution for diagnostic z-scores in the range from 2 to 6. Using the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm, Z-curve estimates the optimal weights for seven components located at z-values of 0, 1, …. 6 to fit the observed statistically significant z-scores. The predicted distribution is shown as a blue curve. Importantly, the model is fitted to the significant z-scores, but the model predicts the distribution of non-significant results. This makes it possible to examine publication bias (i.e., selective publishing of significant results). Using the estimated distribution of non-significant and significant results, z-curve provides an estimate of the expected discovery rate (EDR); that is, the percentage of significant results that were actually obtained without selection for significance. Using Soric’s (1989) formula the EDR is used to estimate the false discovery risk; that is, the maximum number of significant results that are false positives (i.e., the null-hypothesis is true).

Selection for Significance

The extent of selection bias in a journal can be quantified by comparing the Observed Discovery Rate (ODR) of 69%, 95%CI = 69% to 70% with the Expected Discovery Rate (EDR) of 24%, 95%CI = 17%-34%. The ODR is notably higher than the upper confidence interval limit for the EDR, indicating statistically significant publication bias. Furthermore, there is clear evidence of selection for significance given that the ODR estimate is more than double the point estimate of the EDR.

It is also noteworthy that the present results probably underestimate severity of selection bias for focal hypothesis test. The present results do no distinguish between theoretically important and complementary analyses. It is known that focal hypothesis tests in psychology before the replication crisis have an observed success rate over 90% (Sterling, 1959; Sterling et al., 1995; Motyl et al., 2017). While it is possible that focal tests also have higher power, it is likely that the differences in the ODR larger than the differences in the EDR.

In conclusion, the present results are consistent with the finding that replication studies are more likely to produce non-significant results than reported original findings because selection for significance inflates the percentage of significant results in published articles (OSC, 2015).

Expected Replication Rate

The Expected Replication Rate (ERR) estimates the percentage of studies that would produce a significant result again if exact replications with the same sample size were conducted. A comparison of the ERR with the outcome of actual replication studies shows that the ERR is higher than the actual replication rate (Schimmack, 2020). Several factors can explain this discrepancy, including the difficulty of conducting exact replication studies. Thus, the ERR is an optimist estimate. A conservative estimate is the EDR. The EDR predicts replication outcomes if significance testing does not favour studies with higher power (larger effects and smaller sampling error) because statistical tricks make it just as likely that studies with low power are published. We suggest using the EDR and ERR in combination to estimate the actual replication rate.

The Expected Replication Rate (ERR) estimates the percentage of studies that would produce a significant result again if exact replications with the same sample size were conducted. A comparison of the ERR with the outcome of actual replication studies shows that the ERR is higher than the actual replication rate (Schimmack, 2020). Several factors can explain this discrepancy, such as the difficulty of conducting exact replication studies. Thus, the ERR is an optimist estimate. A conservative estimate is the EDR. The EDR predicts replication outcomes if significance testing does not favour studies with higher power (larger effects and smaller sampling error) because statistical tricks make it just as likely that studies with low power are published. We suggest using the EDR and ERR in combination to estimate the actual replication rate.

The ERR estimate of 65%, 95%CI = 61% to 68%, suggests that most results should produce a statistically significant, p < .05, result again in exact replication studies. However, the EDR of 24% implies considerable uncertainty about the actual replication rate for studies in this journal and that the success rate can be between 24% and 65%. These estimates can be compared with the actual success rate of replications of social psychological experiments in the Reproducibility Project of 25% (OSC, 2015). While this estimate is based on a small, unrepresentative sample, it does confirm that the replication rate of social psychological experiments can be as low as 1 out of 4 studies. This justifies concerns about the credibility of results published in JESP (see also Schimmack, 2020).

False Positive Risk

The replication crisis has led to concerns that many or even most published results are false positives (i.e., the true effect size is zero or in the opposite direction). The high rate of replication failures, however, may simply reflect low power to produce significant results for true positives and does not tell us how many published results are false positives. We can provide some information about the false positive risk based on the EDR. Using Soric’s formula (1989), the EDR can be used to calculate the maximum false discovery rate.

The EDR of 24% implies a False Discovery Risk (FDR) of 17%, 95%CI = 10% to 25%, but the 95%CI of the FDR allows for up to 25% false positive results. This estimate contradicts claims that most published results are false (Ioannidis, 2005), but the results also create uncertainty about the credibility of results with statistically significant results, if up to 1 out of 4 results can be false positives. For readers it may be difficult to decide whether a published results can be trusted.

Time Trends

One advantage of automatically extracted test-statistics is that the large number of test statistics makes it possible to examine changes in publication practices over time. We were particularly interested in changes in response to awareness about the replication crisis in recent years.

Z-curve plots for every publication year were calculated to examine time trends through regression analysis. Additionally, the degrees of freedom used in F-tests and t-tests were used as a metric of sample size to observe if these changed over time. Both linear and quadratic trends were considered. The quadratic term was included to observe if any changes occurred in response to the replication crisis. That is, there may have been no changes from 2000 to 2015, but increases in EDR and ERR after 2015.

Degrees of Freedom

Figure 2 shows the median and mean degrees of freedom used in F-tests and t-tests reported in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. The mean results are highly variable due to a few studies with extremely large sample sizes. Thus, we focus on the median to examine time trends. The median degree of freedom over time was 82.25, ranging from 60 to 302. Regression analyses of the median showed a significant linear increase by about 9 degrees of freedom per year, b = 9.13, SE = 0.62, p < 0.0001. Furthermore, there was a statistically significant non-linear increase, b = 0.94, SE = 0.10, p < 0.0001, suggesting that the replication crisis led to an increase in sample sizes. As larger samples increase power, we would expect an increase in the ERR and EDR.

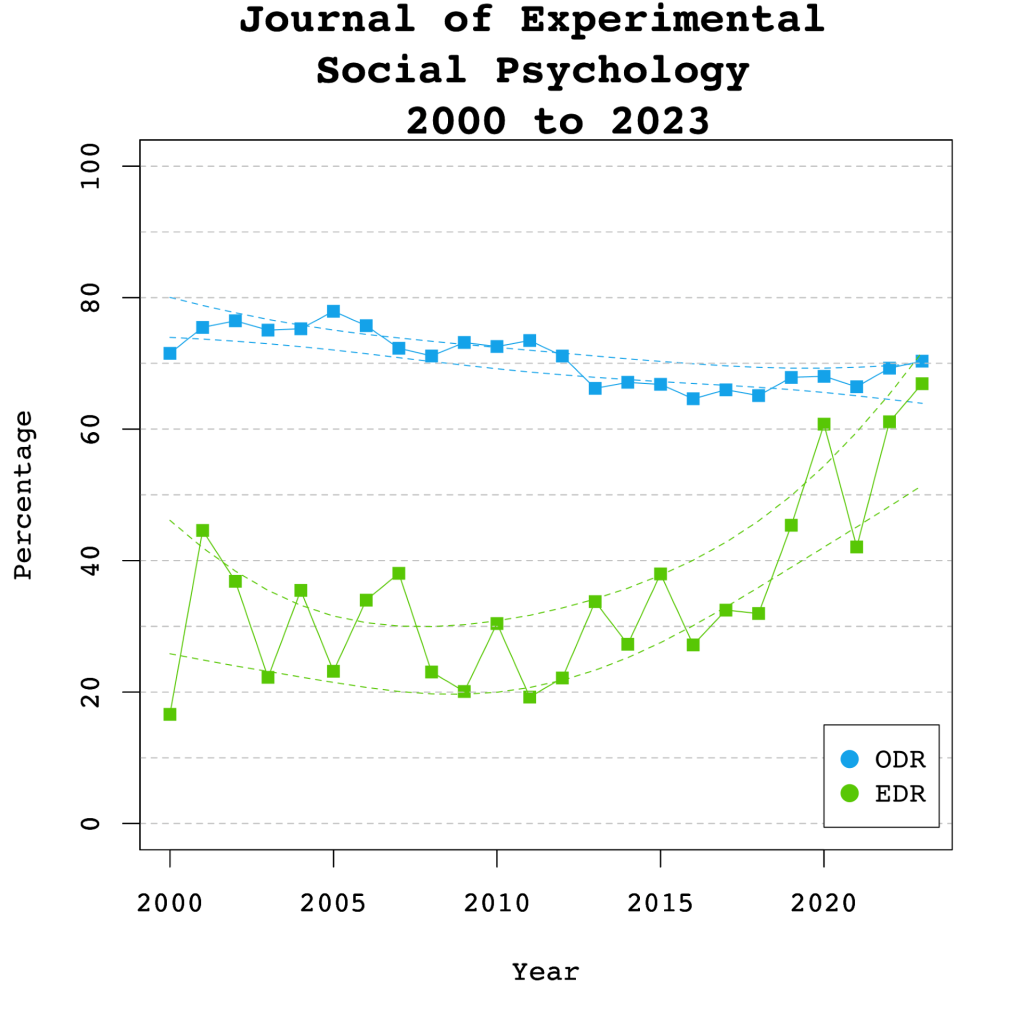

Observed and Expected Discovery Rates

Figure 3 shows the changes in the ODR and EDR estimates over time. There was a significant linear decrease to the ODR estimate by 0.44 percentage points per year, b = -0.44, SE = 0.08, p < 0.0001. No significant non-linear, b = 0.01 (SE = 0.01, p = 0.27) trend was observed in the ODR estimate. These results show that researchers have published more non-significant results over time, leading to a decrease in selection bias.

The regression results for the EDR estimate showed significant linear, b = 1.14 (SE = 0.25 p < 0.001) and non-linear, b = 0.17 (SE = 0.04 p < 0.001) changes over time. The non-linear trend is consistent with the results for the degrees of freedom and confirms that power has increased after the replication crisis due to the use of larger samples. This also reduces selection bias. The trends for the ODR and EDR have narrowed the gap between the ODR and the EDR as seen in Figure 3. However, it remains to be seen whether this trend also applies to focal hypothesis tests.

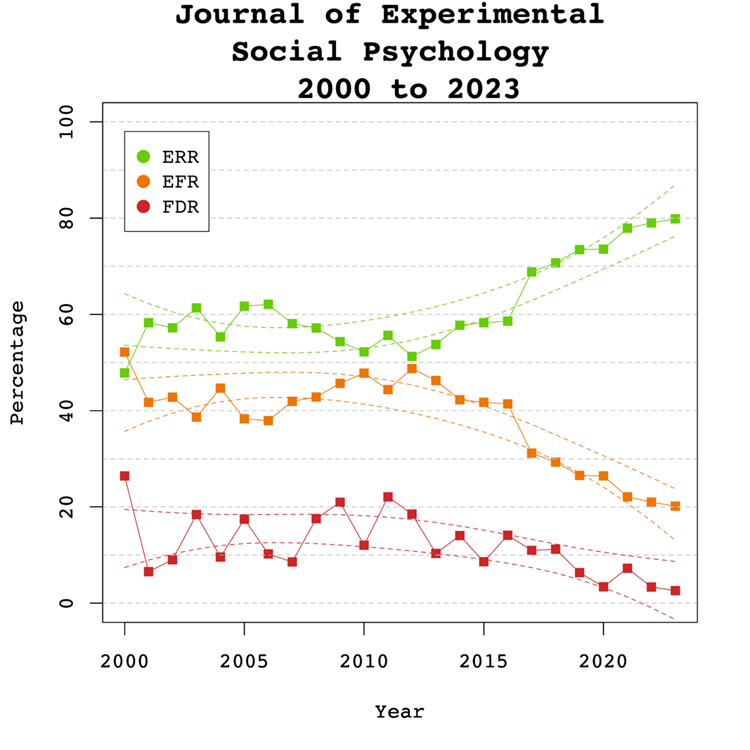

Expected Replicability Rates and False Discovery Risks

Figure 4 depicts the false discovery risk (FDR) and the Estimated Replication Rate (ERR). It also shows the Expected Replication Failure rate (EFR = 1 – ERR). A comparison of the EFR with the FDR provides information for the interpretation of replication failures. If the FDR is close to the EFR, many replication failures may be due to false positive results in original studies. In contrast, if the FDR is low, most replication failures will likely be false negative results in underpowered replication studies.

There were no significant linear, b = 0.13, SE = 0.10, p = 0.204 or non-linear, b = 0.01, SE = 0.16, p = 0.392 trends observed in the ERR estimate. These findings are inconsistent with the observed significant increase in sample sizes as the reduction in sampling error often increases the likelihood that an effect will replicate. One possible explanation for this is that the type of studies has changed. If a journal publishes more studies from disciplines with large samples and small effect sizes, sample sizes go up without increasing power. Thus, analysis of sample size alone provide insufficient information about the credibility of published results.

Visual inspection of Figure 4 depicts the EFR consistently around 30% and the FDR around 10%, suggesting that about one-third of replication failures are false positive results in original studies. The larger decrease for the EFR than the FDR suggests that larger samples have mainly reduced false negative results and increasing the probability that a replication failure reveals a false positive result in the original study.

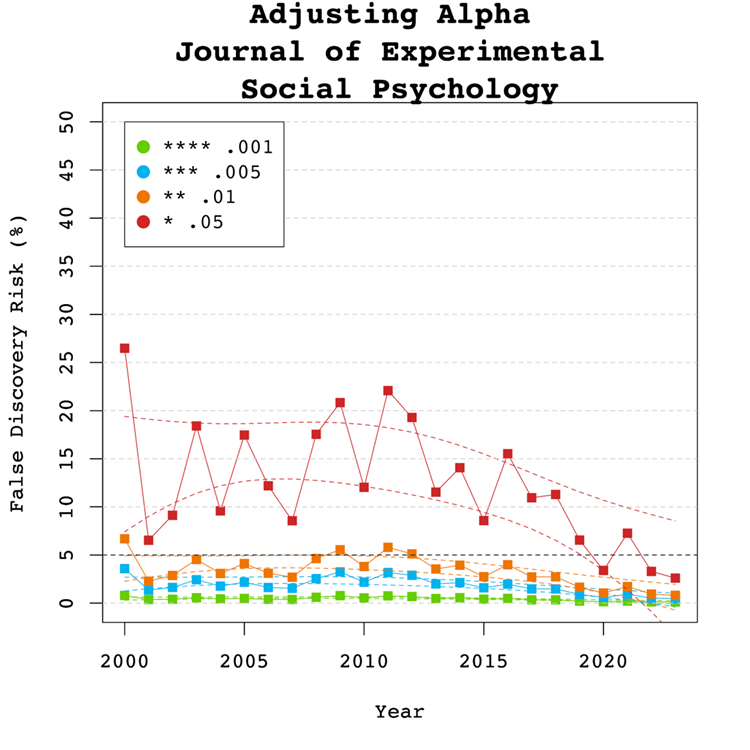

Adjusting Alpha

A simple solution to a crisis of confidence in published results is to adjust the criterion to reject the null-hypothesis. For example, some researchers have proposed to set alpha to .005 to avoid too many false positive results. With z-curve we can calibrate alpha to keep the false discovery risk at an acceptable level without discarding too many true positive results. To do so, we set alpha to .05, .01, .005, and .001 and examined the false discovery risk.

Figure 5 shows that the conventional criterion of p < .05 produces false discovery risks above 5%. The high variability in annual estimates also makes it difficult to provide precise estimates of the FDR. However, adjusting alpha to .01 is sufficient to produce an FDR with tight confidence intervals below 5%. More conservative readers might adjust to p < 0.005 for results published between 2007 and 2013. Overall, the benefits of reducing alpha further to .005 or .001 are minimal.

Figure 6 shows the impact of lowering the significance criterion, alpha, on the discovery rate (lower alpha implies fewer significant results). In the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology lowering alpha to .01 reduces the observed discovery rate considerably in the years before the replication crisis from about 70-80% to just 40-50% of reported results. The reason is that statistical tricks are more likely to produce just significant results between .05 and .01 than lower p-values (Simmons et al., 2011). Therese results are also much less likely to replicate (OSC, 2015). Thus, it is reasonable to treat these results as not significant and to require a credible replication study. In recent years, more p-values are below .01 and using alpha = .01 as significance criterion has relatively little impact on the discovery rate. Lowering alpha further has relatively little effect on the discovery rate. While these results should not be interpreted as a call for official changes to the alpha criterion, they help readers to evaluate the costs and benefits of using a specific alpha level. We believe that alpha = .01 provides an optimal trade-off for results published in JESP.

Limitations

One concern about the publication of our results is that it merely creates a new criterion to game publications. Rather than trying to get p-values below .05, researchers may use tricks to get p-values below .01. However, this argument ignores that it becomes increasingly harder to produce lower p-values with tricks (Simmons et al., 2011). Moreover, z-curve analysis makes it easy to see selection bias for different levels of significance. Thus, a more plausible response to these results is that researchers will increase sample sizes or use other methods to reduce sampling error to increase power. Our trend analyses show that this has already happened and that results published after 2015 are more credible.

A bigger concern is that our results underestimate the severity of the problem because they do not distinguish between theoretically important (focal) and additional (non-focal) hypothesis tests. To address this concern it is necessary to identify focal hypothesis tests and to hand-code results of these tests. For JESP, we were able to use hand-coded data from Motyl et al.’s (2017) article that randomly selected focal hypothesis tests from several journals, including JESP. The data are based on the years 2003, 2004, 2013, and 2014 and are representative for the years before reforms increased replicability (see Figures 3 & 4).

The ODR is similar to the ODR for all test statistics (70% vs. 69%, but non-significant results are clustered just below the significance level of .05 and are often used to reject the null-hypothesis with “marginal significance” (p < .10, z > 1.65). If these results are counted as ‘significant’, the ODR is 87%, which is close to Sterling et al.’s (1995) findings that over 90% of hypothesis tests in psychology reject the null-hypothesis. In contrast, the estimate of the expected discovery rate is only 14%, which is lower than the estimate for all hypothesis tests (Figure 1, 24%). Although the small number of studies leads to wide confidence intervals, the results suggest that focal tests have even lower power than other tests. The confidence interval for the EDR even includes 5%, which would imply that power equals alpha, which is the case when the population effect sizes are zero. This also implies that the confidence interval for the FDR includes 100%, suggesting that all focal hypothesis are false. Of course, it is unlikely that social psychologists only reported false results for decades, but the evidence is so weak that it is impossible to know which of these results are true and which ones are false. In this case, adjusting alpha does not help because the upper limit of the FDR confidence interval remains at 100% because the lower bound of the confidence interval for the EDR remains at 5%. Until more evidence for focal tests is obtained, it may be justified to use the results for all tests, but the false discovery risk for focal tests with p-values below .01 may be higher than 5%. Given so much uncertainty about results published in JESP before 2015, single studies should not be interpreted and important studies should be replicated with larger samples and preregistration.

Conclusion

The replicability report for the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology suggests that the power to obtain a significant result to report a significant result (i.e., a discovery) ranges from 24% to 65%, and may be even lower for focal hypothesis tests. This finding suggests that many studies are underpowered and require luck to get a significant result. The false positive risk is considerable but can be controlled by setting alpha to .01 during most years. However, an analysis of a small set of focal tests suggests that this criterion is too liberal for focal tests, but it is impossible to quantify the false discovery risk for focal tests.

Our results show clear evidence of improvement in response to the replication crisis. Power has increased with the help of larger samples and selection bias has decreased. This is a welcome development. It also means that our recommendation to use alpha of .01 penalizes only a smaller set of studies with p-values between .05 and .01. Of course, these results can occur by chance and can be false negatives, but in this case researchers should conduct additional studies to strengthen evidence for their hypothesis.

Hand-coding of focal tests after 2015 would provide important information about the credibility of focal tests in recent years. One important question is whether the journal publishes studies with non-significant results in large samples that suggest a hypothesis was false. These results would best be reported with 95%CI that limit plausible effect sizes to values close to zero. After all, risky hypotheses are bound to be false sometimes.

In conclusion, our results provide some valuable empirical evidence about the credibility of results published in JESP. The main finding is that results before the replication crisis had low credibility and were often obtained by selectively reporting confirmatory evidence. This has changed and results in recent years have much less selection bias and are more credible.