We are running out of terms. Personomics, Personmetrics, and Personometrics have already been used. Fortunately, the term Personometrics is used by engineers to talk about people as data sources. I hope they are fine with me using the same term to describe the marriage of personality science with psychometrics.

Psychologists are of course used to fake novelty and it seems fair to accuse me of just trying to be original by finding a new term for something that is not novel at all. Don’t we already have journals with titles like “Journal of Personality Assessment,” or “European Journal of Psychological Assessment?” However, a WebOfScience search with “personality” and “measurement” retrieves only 624 articles and the article with the 7th highest citation count is a article by situationist Walter Mischel from 1977 with the title “The future of personality measurement.” For people unfamiliar with personality psychology, it is necessary that Mischel is best known for his claim that personality traits do not exist, which makes the measurement of personality unnecessary. The lack of influential and foundational articles on personality measurement suggests that personometrics is indeed a neglected research topic.

Another indication that personality research and mesurement are separate fields is an article by a psychometrician that criticized personality psychologists for their lack of understanding of modern psychometrics (Borsboom, 2006). Borsboom’s article attacked McCrae, Zonderman, Costa, Bond, and Paunonen (1996) for their conclusion that modern psychometrics should not be used to study personality because these methods do not support their theory of personality structure. You do not have to be a rocket scientist to realize that rejecting a method because it fails to support your theory is not science. Science requires testing theories and revising theories when a theory does not predict empirical observations. Thus, McCrae et al.’s rejection of modern measurement theory is unscientific. If would not be necessary to mention this article, if it were not symptomatic of the attitude towards psychometrics among personality psychologists even today. Twenty years after McCrae published the infamous article, he wrote to me and argued “Why in the world do you think that “CFA is the only method that can be used to test structural theories”? If that were true, I would agree with your position. But the major point of our paper was to offer an alternative confirmatory approach using targeted rotation” (McCrae, personal communication, 2019).

This response shows that McCrae still did not understand the fundamental difference between the classic and outdated methods they used and modern latent variable models that are now commonly used in psychometrics (Borsboom, 2006). He also seems to be unaware of Borsboom’s criticism of the 1996 article. As a result, a peer-reviewed psychometric evaluation of Costa and McCrae’s model of personality is still lacking in 2025 (see Schimmack, 2019a, 2019b, 2019c, 2024, for pre-prints).

Other personality psychologists share this attitude towards psychometrics. In another personal communication, Lew Goldberg wrote “Isn’t it the case that one problem with CFA is that one must start with an ending? That is, one must have a structural representation in mind before one can “confirm” it. EFA might be used to provide the initial structure in novel domains, and then one might use CFA as a more “causal” representation?”

The statement also reveals a fundamental lack of understanding of psychometric models like Confirmatory Factor Analysis. First, it is an entirely different model than EFA that does not allow for hierarchical structures or correlated residuals. Thus, EFA may never produce results that can fit the data with a CFA analysis. Second, it is not a problem that CFA requires an idea about the structure in the data. In fact, this is the the main strength of CFA. It may confirm or disconfirm a theory depending on the fit to the data. In contrast, EFA does not test theories and fails to alert users that the simplistic model does not fit the data. The main problem that McCrae et al. (1996) encountered was not a lack of a theory, but the lack of fit of their theory to the data.

Bill Revelle also sent me an email to inform me that EFA is fine and, contrary to my claims, can fit hierarchical models. “Inspired by your blog on how one needs to use CFA to do hierarchical models (which is in fact, incorrect), I prepared the enclosed slides.”

It is not necessary to discuss Revelle’s EFA approach to the study of hierarchical structures because he has never attempted to use this approach to study personality traits. Instead, he has warned about the use of latent variable models which includes EFA and CFA and is now advocating the study of personality items rather than personality traits. This is like studying thermometers without a theory of temperature.

I hope these three examples of prominent personality researchers support my claim that personality psychologists have shown little interest in using statistical methods developed by psychometricians to test theories and evaluate measures. Thus, Borsboom’s attack has had no effect on research practices in personality research.

Borsboom also contributed to the lack of progress in personality measurement because he convinced himself that personality traits do not exist. In a series of papers, Borsboom examined crucial concepts like latent variables and construct validity. He came to the right conclusoin that measurement is based on a causal effect of a factor that exist independent of a measure on an instrument that was created to reflect variation in the factor. Cronbach and Meehl (1955) used temperature and thermometers as an example. Temperature is a physical attribute of the material world and thermometers are valid if variation in the reading on the thermometer corresponds to the variation in temperature.

The same assumption is made in personality psychology. The problem is that the influence of personality traits on observable behaviors is not deterministic. Behavior is always a function of situational factors and personality factors. This makes it harder to measure personality. Another problem is that the internal causes of behavior are not directly observable because they are rooted in complex neurological processes. This makes it difficult or impossible to experimentally manipulate personality traits to study their effects on behavior and to validate personality measures. These difficulties, however, do not justify disbelief in the reality of personality traits. Twin studies, for example, have provided strong evidence that some internal causes of behavior are heritable. It is also possible to observe the influence of personality by demonstrating consistency in behavior across different situations. Borsboom ignored all of this evidence from decades of personality research to claim that personality traits are not real and to claim that it is wrong to model item correlations with latent variables. Thus, he also dismissed the use of psychometric measurement models to study personality (Cramer et al., 2013).

Thus, here we are in 2025 without empirically tested theories of personality traits and validated measures of these traits. This problem is hidden by the fact that personality researchers pretend that they study personality traits and routinely claim that their personality scales are valid. The problem is that the term validity itself has no meaning (Schimmack, 2020). A classic article by Cronbach and Meehl (1955) introduced the concept of construct validity. A measure has construct validity, if it measures what it is supposed to measure. To evaluate whether a measure is a valid measure of a construct, it is necessary to define a construct. For example, to evaluate the construct validity of a measure of Extraversion, it is necessary to define Extraversion. The problem for personality researchers is that 100 years of research on Extraversion has not produced an answer to the question of the nature of extraversion. What is extraversion?

The lack of a theory of extraversion or any other personality trait is not a problem for personality researchers because they operationalize construct. That is, the concept is defined by the measure. Extraversion is whatever a specific Extraversion scale measures. Typically, this means that Extraversion is defined by a specific set of items that a personality researcher wrote. This classic approach to the study of personality is illustrated in Figure 1a.

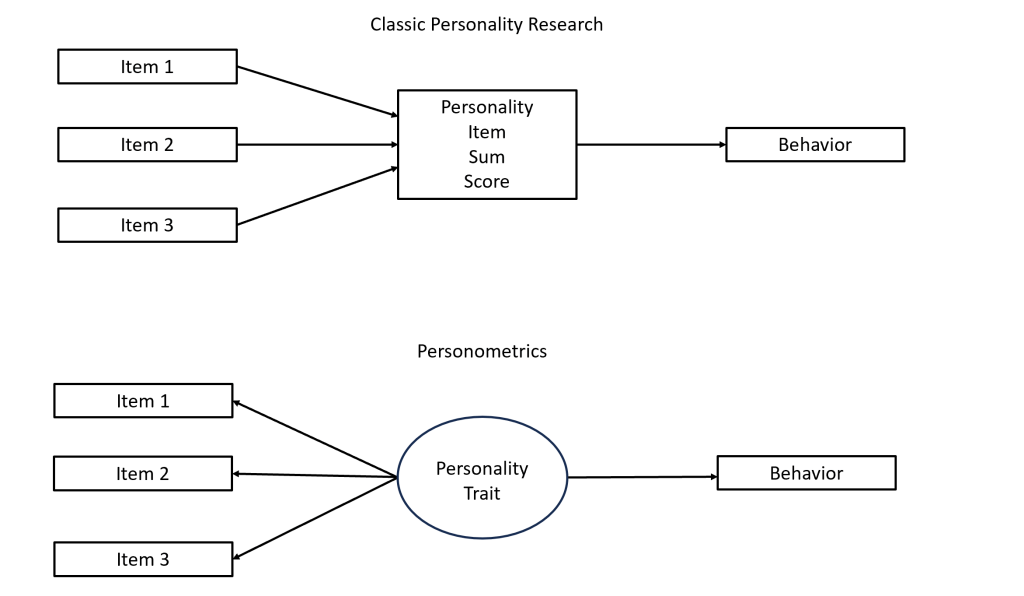

Figure 1 uses the graphic language of structural equation modeling to illustrate the difference between classic personality research that is grounded in classic test theory and psychonometrics, which is rooted in modern psychometrics.

In classic test theory, constructs are operationalized by specific operations that produce scores for individuals. The typical operation in personality research is to ask participants for a rating on a Likert scale. In Figure 1, there are three items. To reduce random measurement error, the scores to the three items are summed or averaged. In the picture this operation is illustrated by the arrows pointing from the items to the sum score. Evidently, scores on the sum score depend on the specific items. Different sets of items will produce different sum scores. Operationalism is captured in saying like “Intelligence is whatever the intelligence test measures.” As there is no theoretical construct that exists independent of the specific items, it is meaningless to question the construct validity of a sum score. A sum score is a sum score is a sum score.

Operationalism is often masked in the cargo cult of classic personality research by naming their sum scores with worlds that are used in everyday language (Anxiety) or can be interpreted using everyday language (Positive Affect, Psychological Wellbeing). This practice is problematic because it seems to imply that sum scores measure constructs and that the construct is captured by the everyday meaning of the labels. The problem with operationalism is that there is no way to examine construct validity; that is, does a sum score really measure what it label suggests. As a result, personality item sum scores have unknown construct validity (Borsboom, 2006; Schimmack, 2010).

To give an example, I am using three of the 10 items from the Positive Affect (PA) scale of the Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The items are strong, attentive, and active. We sum the scores on the three items and now we call the sum score Positive Affect. Using this sum score, we find lower scores of PA on weekends than during the week. The result is used to provide scientific evidence for the claim that people have higher Positive Affect during the week than on the weekend. If you think this is a problem, you made the mistake to assume that a Positive Affect sum score measures something like happiness or pleasure based on your interpretation of the worlds Positive Affect. The correct interpretation is that people have more of whatever the PA sum score measures during the week than on the weekend. At best we can look at the item content and say that people are more likely to be active, attentive, and strong during the week than on the weekend. However, even this conclusion may be wrong because the sum score is compatible with different patterns for the individual items. Maybe only attentiveness and activity are higher during the week, but strong shows the reverse pattern. To be sure, we would have to examine each item individually and then the result for the sum score follows directly from the pattern of the differences for each item.

The next problem of classic personality research is that it blurs the distinction between prediction and causation. The reason is that personality research often uses correlational evidence because it is difficult or unethical to manipulate personality traits. Psychology has a strong bias towards experimental evidence as evidence to support causal claims. To justify the use of artificial and simplistic laboratory experiments, correlational studies are often criticized for not being able to prove causality. As a result, personality researchers are very reluctant to talk about causality. Even when they want to make causal claims, they often avoid causal language or editors tell them to avoid causal language. As no evidence of causality is needed, correlational results are considered sufficient. Even when causality is implied, it is sufficient to claim that some unspecified experiment is needed to provide evidence of causality in the future.

Personometrics requires causal assumptions. First, the measurement model implies that variation in an unobserved personality traits causes variation in item responses to use item responses as valid measures of a personality trait. Second, personometrics makes causal claims because it assumes that variation in personality traits causes variation in actual behaviors (Figure 1b). The assumption that correlations between item responses and behaviors are caused by a common personality trait makes it possible to test construct validity of personality measures. For example, to demonstrate that a shyness questionnaire measures shyness, researchers can examine behavioral indicators of shyness in a controlled laboratory setting (Asendorpf & Banse, 2002).

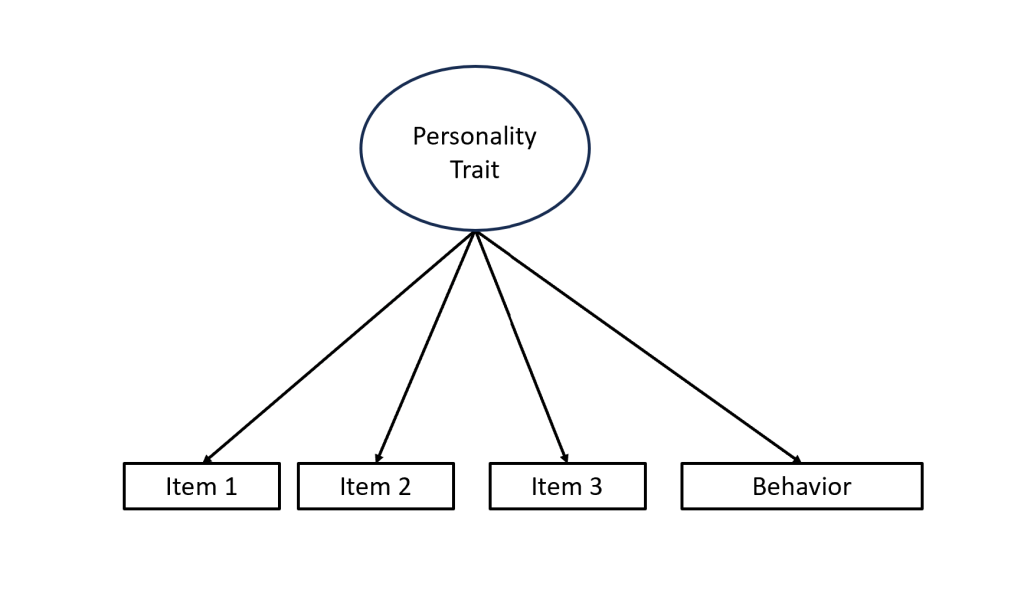

Figure 2 is a different visual representation of the psychonometric model in Figure 1b. It highlights that there is no structural distinction between real world behaviors and responses to test items in a survey. Every observable variable can serve as an indicator that reflects the influence of a personality trait. A shyness item is a good measure of shyness if it shares variance with variation in actual shyness behaviors. The stronger the relationship is, the higher is an item’s validity. The common cause model is the fundamental principle in Cronbach and Meehl’s (1955) seminal article on construct validity.

The validation with specific behaviors or feelings in a specific situation (states) is useful because it is much easier to define constructs of observable behaviors. For example, while the internal mental and neurological processes that produce variation in helpfulness are difficult to study, it is a lot easier to define behaviors like helping. Even without insights into the inner processes, it is then possible to measure trait differences by observing behaviors in controlled situations or as cross-situational consistency across independent situations in real life (Schimmack, 2010). Self-report measures mainly serve the purpose of making the measurement of these traits easier and cheaper. That is, once a set of items has been validated as a measure of a personality trait, variation in the measure can be used to test theories of the causes and consequences of personality traits.

The model in Figure 2 makes it clear that latent variables are needed to build theories of personality that can explain behavior. The reason is that item-responses are not causes of behavior. The only justification for the use of item-responses as predictors of behavior is the assumption that item-responses reflect unobserved causes of actual behaviors. This fundamental assumption requires validation by demonstrating that correlations among items and correlations of items with actual behaviors and other relevant variables are consistent with a theory of internal causes of behavior.

Some personality psychologists have argued that latent variable models have many problems that make it less appealing to use them (McCrae et al., 1996). Many of these criticism are outdated and based on lack of expertise. While latent variable models may have a steep learning curve, they offer a lot of advantages over classic correlational studies with sum scores. First, it is well known that short scales with a few items have low reliability. To address this problem with sum scores researchers often use scales with 4, 8, or 10 items. However, this limits the amount of traits that can be measured. Latent variable models correct for unreliability and it is possible to measure a trait with just three items. It is also known that self-report items are biased by response styles. Correcting for these response styles with sum scores is difficult and so called lie scales do not work. In contrast, latent variable models make it possible to correct for systematic biases and to measure them with just a few items (Anusic et al., 2009). Finally, latent variable models are needed when personality traits are measured with multiple methods or ratings by multiple raters. A sum score will reduce rater-biases, but it will not eliminate the individual biases. In contrast, a latent variable model makes it possible to separate the shared variance among raters that is more likely to reflect the true trait from rater-specific variance that is more likely to be measurement error. In short, latent variable models are needed to move personality research forwards towards personality science. The hallmark of science is to use methods that subject theories to empirical tests and can force researchers to revise and improve their theories. Personometrics takes this fundamental aspect of science seriously. Traditional personality researchers like McCrae, Goldberg, and Revelle may not want to embrace modern methods, but hopefully new psychologists who are interested in internal causes of behavior will break with the anti-science dogma and embrace falsification of untested personality theories like the Big Five model.

References

Asendorpf, J. B., Banse, R., & Mücke, D. (2002). Double dissociation between implicit and explicit personality self-concept: the case of shy behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology, 83(2), 380–393.

Borsboom, D. (2006). The attack of the psychometricians. Psychometrika, 71(3), 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-006-1447-6

Borsboom, D., Mellenbergh, G. J., & van Heerden, J. (2003). The theoretical status of latent variables. Psychological Review, 110(2), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.203

Cramer, A. O. J., Van der Sluis, S., Noordhof, A., Wichers, M., Geschwind, N., Aggen, S. H., Kendler, K. S., & Borsboom, D. (2012). Dimensions of normal personality as networks in search of equilibrium: You can’t like parties if you don’t like people. European Journal of Personality, 26(4), 414–431. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1866