In the 17th century, early telescopic observations of Mars suggested that the planet might be populated. Now imagine a study that aims to examine whether Martians are taller than humans. The problem is obvious: although we may assume that Martians exist, we cannot observe or measure them, and therefore we end up with zero observations of Martian height. Would we blame the t-test for not telling us what we want to know? I hope your answer to this rhetorical question is “No, of course not.”

If you pass this sanity check, the rest of this post should be easy to follow. It responds to criticism by Erik van Zwet (EvZ), hosted and endorsed by Andrew Gelman on his blog,

“Concerns about the z-curve method.”

EvZ imagines a scenario in which z-curve is applied to data generated by two distinct lines of research. One lab conducts studies that test only true null hypotheses. While exact effect sizes of zero may be rare in practice, attempting to detect extremely small effects in small samples is, for all practical purposes, equivalent. A well-known example comes from early molecular genetic research that attempted to link variation in single genes—such as the serotonin transporter gene—to complex phenotypes like Neuroticism. It is now well established that these candidate-gene studies produced primarily false positive results when evaluated with the conventional significance threshold of α = .05.

In response, molecular genetics fundamentally changed its approach. Researchers began testing many genetic variants simultaneously and adopted much more stringent significance thresholds to control the multiple-comparison problem. In the simplified example used here, I assume α = .001, implying an expected false positive rate of only 1 in 1,000 tests. I further assume that truly associated genetic predictors—single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)—are tested in very large samples, such that sampling error is small and true effects yield z-values around 6. This is, of course, a stylized assumption, but it serves to illustrate the logic of the critique.

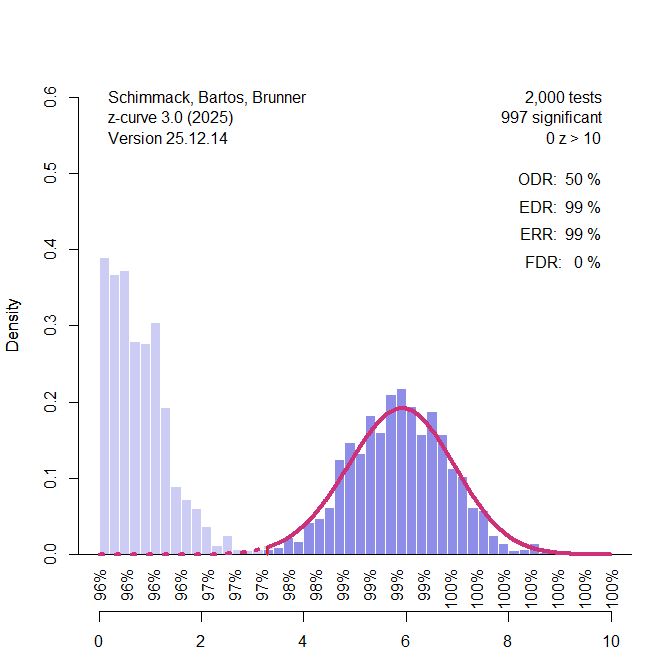

Figure 1 illustrates a situation with 1,000 studies from each of these two research traditions. Among the 1,000 candidate-gene studies, only one significant result is expected by chance. Among the genome-wide association studies (GWAS), power to reject the null hypothesis at α = .001 is close to 1, although a small number (3–4 out of 1,000) of studies may still fail to reach significance.

At this point, it is essential to distinguish between two scenarios. In the first scenario, all 999 non-significant results are observed and available for analysis. If we could recover the full distribution of results—including non-significant ones—we could fit models to the complete set of z-values. Z-curve can, in principle, be applied to such data, but it was not designed for this purpose.

Z-curve was developed for the second scenario. In this scenario, the light-purple, non-significant results exist only in researchers’ file drawers and are not part of the observed record. This situation—selection for statistical significance—is commonly referred to as publication bias. In psychology, success rates above 90% strongly suggest that statistical significance is a necessary condition for publication (Sterling, 1959). Under such selection, non-significant results provide no observable information, and only significant results remain. In extreme cases, it is theoretically possible that all published significant findings are false positives (Rosenthal, 1979), and in some literatures—such as candidate-gene research or social priming—this possibility is not merely theoretical.

Z-curve addresses uncertainty about the credibility of published significant results by explicitly conditioning on selection for significance and modeling only those results. When success rates approach 90% or higher, there is often no alternative: non-significant results are simply unavailable.

In Figure 1, the light-purple bars represent non-significant results that exist only in file drawers. Z-curve is fitted exclusively to the dark-purple, significant results. Based on these data, the fitted model (red curve), which is centered near the true value of z = 6, correctly infers that the average true power of the studies contributing to the significant results is approximately 99% when α = .001 (corresponding to a critical value of z ≈ 3.3).

Z-curve also estimates the Expected Discovery Rate (EDR). Importantly, the EDR refers to the average power of all studies that were conducted in the process of producing the observed significant results. This conditioning is crucial. Z-curve does not attempt to estimate the total number of studies ever conducted, nor does it attempt to account for studies from populations that could not have produced the observed significant findings. In this example, candidate-gene studies that produced non-significant results—whether published or not—are irrelevant because they did not contribute to the set of significant GWAS results under analysis.

What matters instead is how many GWAS studies failed to reach significance and therefore remain unobserved. Given the assumed power, this number is at most 3–4 out of 1,000 (<1%). Consequently, an EDR estimate of 99% is correct and indicates that publication bias within the relevant population of studies is trivial. Because the false discovery rate is derived from the EDR, the implied false positive risk is effectively zero—again, correctly so for this population.

EvZ’s criticism of z-curve is therefore based on a misunderstanding of the method’s purpose and estimand. He evaluates z-curve against a target that includes large numbers of studies that leave no trace in the observed record and have no influence on the distribution of significant results being analyzed. But no method that conditions on observed significant results can recover information about such studies—nor should it be expected to.

Z-curve is concerned exclusively with the credibility of published significant results. Non-significant studies that originate from populations that do not contribute to those results are as irrelevant to this task as the height of Martians.