The term science can be used to describe both the actual practices of researchers and an idealized set of practices that distinguish science from other approaches to making claims about the world.

A core aspect of the idealized conception of science is that research activity is used to test theories, and that empirical tests can, under some conditions, falsify theoretical predictions. Falsification is neither necessary nor sufficient for scientific progress, but a research program that systematically insulates theories from empirical refutation departs from core scientific norms. Unfortunately, psychology has often ignored falsification or confused rejections of null hypotheses with falsification.

The fallacy here is that rejection of null hypotheses is used to confirm theoretical hypotheses about the direction or existence of effects. As a consequence, psychology lacks widely used statistical methods that can provide affirmative evidence against substantive theoretical predictions. Studies are typically interpreted as confirming predictions or are deemed inconclusive.

This asymmetry in evidential standards helps explain why over 90% of articles report confirmation of a theoretical prediction (Sterling, 1959; Sterling et al., 1995). Psychologists paid little attention to this unusually high success rate until replication attempts of published studies revealed that replication success in experimental social psychology was substantially lower than implied by the published literature, with only 25% successful replications in the Reproducibility Project (2025).

Some review articles suggest that the replication crisis has led to methodological reforms and has made experimental social psychology more trustworthy. This is partially correct. Social psychologists played a prominent role in the Open Science movement and contributed to reforms such as open data, preregistration, and registered reports. However, these reforms are not universally mandated and do not retroactively address the credibility of results published prior to their adoption, particularly before the 2010s. Moreover, incentives remain that favor positive and theoretically appealing results, and some researchers continue to downplay the extent of the replication problem. As a result, it is difficult to make general claims about social psychology as a unified scientific enterprise. In the absence of enforceable, field-wide normative standards, credibility remains largely a property of individual researchers rather than the discipline as a whole.

Social Priming

Priming is a general term in psychology referring to the automatic influence of stimuli on subsequent thoughts, feelings, or behaviors. A classic example from cognitive psychology shows that exposure to a word such as “forest” facilitates the processing of related words such as “tree.”

Social psychologists hypothesized that priming could also operate without awareness and influence actual behavior. A well-known study appeared to show that exposure to words associated with elderly people caused participants to walk more slowly (Bargh et al., 1996). That article also reported subliminal priming effects, suggesting that behavioral influence could occur without conscious awareness. These findings inspired a large literature that appeared to demonstrate robust priming effects across diverse primes, presentation modes, and behavioral outcomes, with success rates comparable to those documented by Sterling (1959).

In 2012, a group of relatively early-career researchers published a failure to replicate the elderly-walking priming effect (Doyen et al., 2012). The publication of this study marked an important turning point, as it challenged a highly influential finding in the literature. Bargh responded critically to the replication attempt, and the episode became widely discussed. Daniel Kahneman had highlighted priming research in Thinking, Fast and Slow and, concerned about its replicability, encouraged original authors to conduct high-powered replications. These replications were not forthcoming, while independent preregistered studies with larger samples increasingly failed to reproduce key priming effects. As a result, priming research became a focal example in discussions of the replication crisis. Kahneman later distanced himself from strong claims based on this literature and expressed regret about relying on studies with small samples (Kahneman, 2017).

Willful Ignorance and Incompetence In Response to Credibility Concerns

In 2016, Albarracín (as senior author) and colleagues published a meta-analysis concluding that social priming effects exist, although the average effect size was relatively small (d ≈ .30; Weingarten et al., 2016). An effect of this magnitude corresponds to roughly one-third of a standard deviation, which is modest in behavioral terms.

The meta-analysis attempted to address concerns about publication bias—the possibility that high success rates reflect selective reporting of significant results. If selection bias is substantial, observed effect sizes will be inflated relative to the true underlying effects. The authors applied several bias-detection methods that are now widely recognized as having limited diagnostic value. They also used the p-curve method, which had been introduced only two years earlier (Simonsohn et al., 2014). However, the p-curve results were interpreted too optimistically. P-curve can reject the hypothesis that all significant results arise from true null effects, but it does not test whether publication bias is present or whether effect sizes are inflated. Moreover, the observed p-curve was consistent with an average statistical power of approximately 33%. Given such power, one would expect roughly one-third of all studies to yield significant results under unbiased reporting, yet the published literature reports success rates exceeding 90%. This discrepancy strongly suggests substantial selective reporting and implies that the true average effect size is likely smaller than the headline estimate.

Sotola (2022) reexamined Weingarten et al.’s meta-analysis using a method called z-curve. Unlike p-curve, z-curve explicitly tests for selective reporting by modeling the distribution of statistically significant results. It is also more robust when studies vary in power and when some studies have true effects while others do not. Whereas p-curve merely rejects the hypothesis that all studies were obtained under a true null, z-curve estimates the maximum proportion of significant results that could be false discoveries, often referred to as an upper bound on the false discovery rate (Bartos & Schimmack, 2022).

Sotola found that priming studies reported approximately 76% significant results—somewhat below the roughly 90% level typically observed in social psychology—but that the estimated average power to produce a significant result was only 12.40%. Z-curve also did not rule out the possibility that all observed significant results could have arisen without a true effect. This finding does not justify the conclusion that social priming effects do not exist, just as observing many white swans does not prove the absence of black swans. However, it does indicate that the existing evidence—including the Weingarten et al. meta-analysis—does not provide conclusive support for claims that social priming effects are robust or reliable. The literature documents many reported effects but offers limited evidential leverage to distinguish genuine effects from selective reporting (many sitings of UFOs, but no real evidence of alien visitors).

Despite these concerns, Weingarten’s meta-analysis continues to be cited as evidence that priming effects are real and that replication failures stem from factors other than low power, selective reporting, and effect size inflation. For example, Iso-Ahola (2025) cites Weingarten et al. while arguing that there is no replication crisis. Notably, this assessment does not engage with subsequent reanalyses of the same data, including Sotola’s z-curve analysis.

This article illustrates what can reasonably be described as willful ignorance: evidence that does not fit the preferred narrative is not engaged. The abstract’s claim that “there is no crisis of replication” is comparable, in terms of evidential standards, to assertions such as “climate change is a hoax”—claims that most scientists regard as unscientific because they dismiss a large and well-documented body of contrary evidence. Declaring the replication problem nonexistent, rather than specifying when, where, and why it does not apply, undermines psychology’s credibility and its aspiration to be taken seriously as a cumulative science.

Willful ignorance is also evident in a recent meta-analysis, again with Albarracín as senior author. This meta-analysis does not include a p-curve analysis and ignores the z-curve reanalysis by Sotola altogether. While the new meta-analysis reports no effects in preregistered studies, its primary conclusion nevertheless remains that social priming has an effect size of approximately d = .30. This conclusion is difficult to reconcile with the preregistered evidence it reports.

A different strategy for defending social priming research is to question the validity of z-curve itself (Pek et al., 2025, preprint, Cognition & Emotion). For example, Pek et al. note that transforming t-values into z-values can break down when sample sizes are extremely small (e.g., N = 5), but they do not acknowledge that the transformation performs well at sample sizes that are typical for social psychological research (e.g., N ≈ 30). Jerry Brunner, a co-author of the original p-curve paper and a professor of statistics, identified additional errors in their arguments (Brunner, 2024). Despite detailed rebuttals, Pek et al. have repeated the same criticisms without engaging with these responses.

This pattern is best described as willful incompetence. Unlike willful ignorance, which ignores inconvenient evidence, willful incompetence involves superficial engagement with evidence while the primary goal remains the defense of a preferred conclusion. In epistemic terms, this resembles attempts to rebut well-established scientific findings by selectively invoking technical objections without addressing their substantive implications.

Z-Curve Analysis of Social Priming

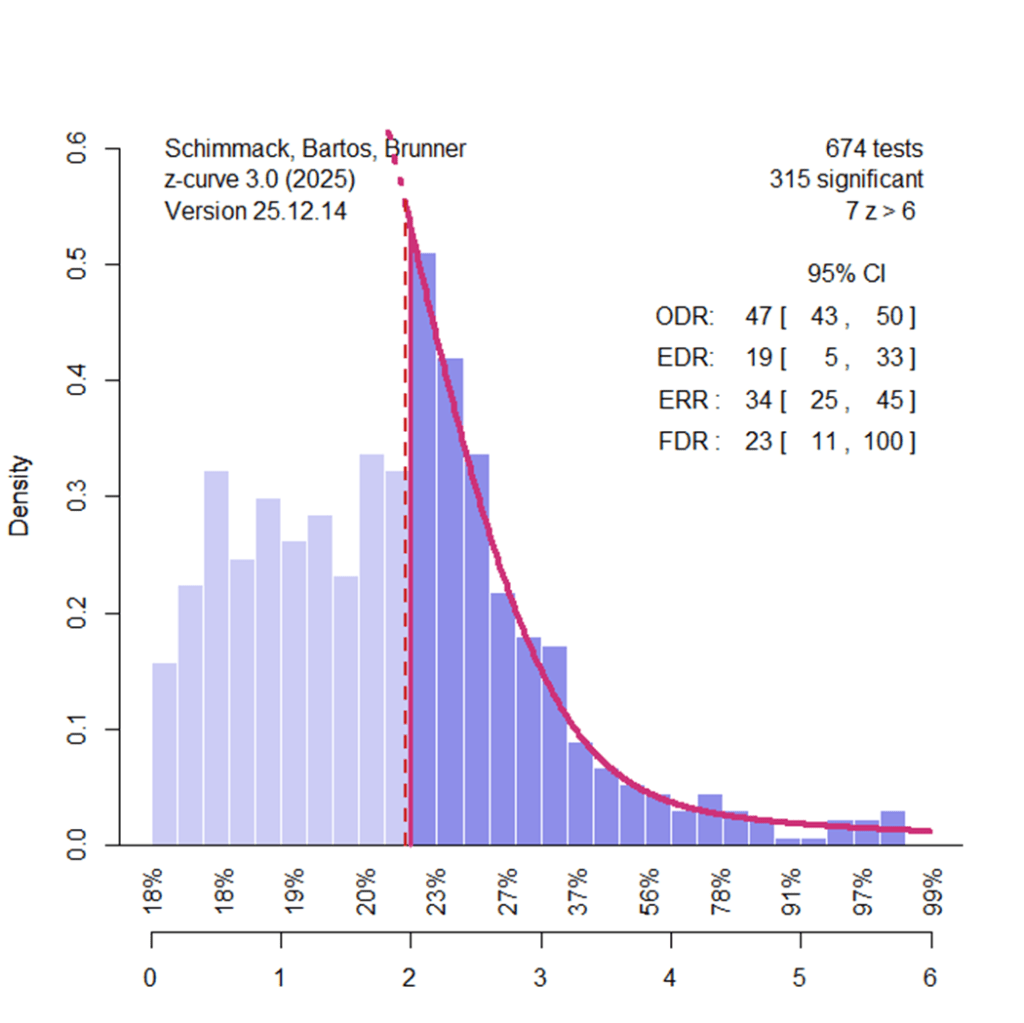

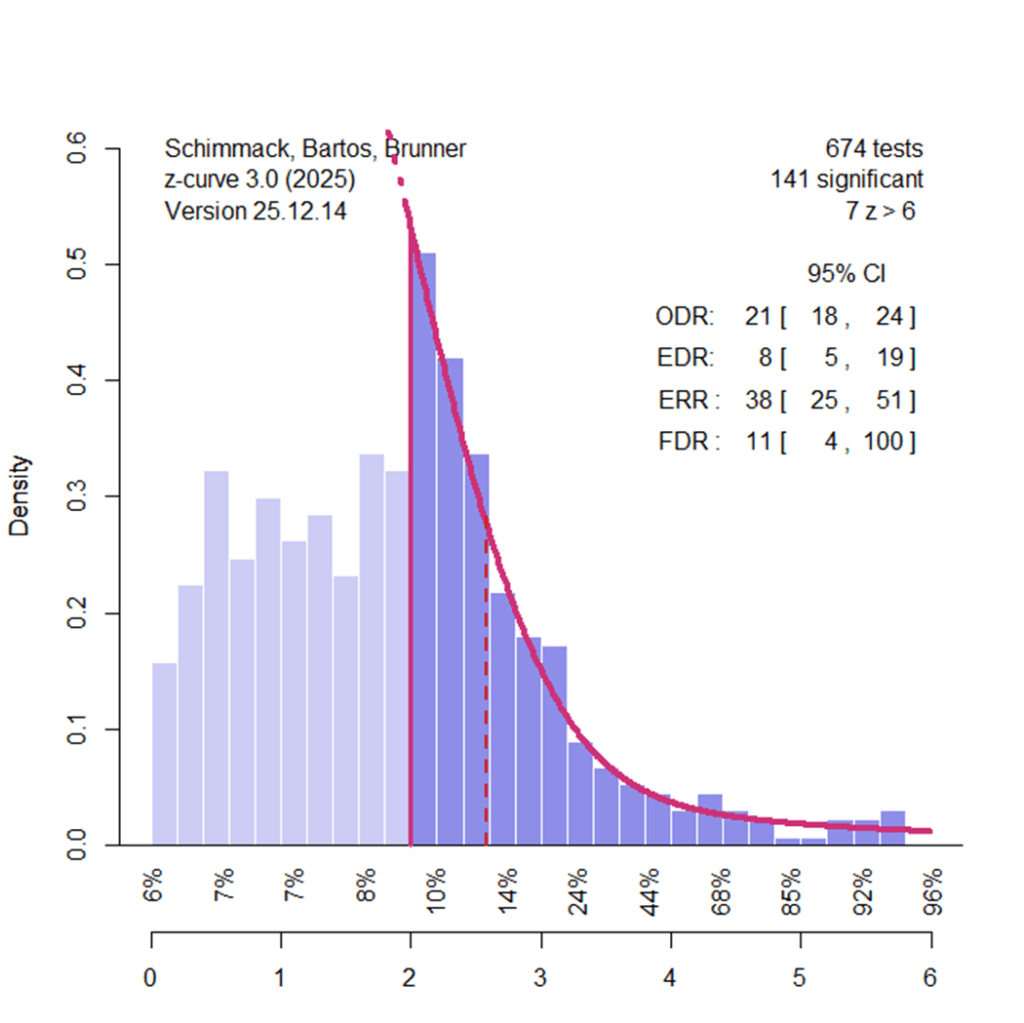

To illustrate how z-curve works and what it reveals about social priming, I analyzed the new meta-analysis of social priming using z-curve. Importantly, I had no influence on the data and only transformed reported information about effect sizes and sampling error into z-values. A z-curve plot provides a descriptive visualization of the evidential strength of published results relative to the null hypothesis. At this descriptive level, few assumptions are required.

The full z-curve analysis fits a statistical model to the distribution of z-values. Studies with low power—due to small effect sizes, small sample sizes, or both—are likely to produce low z-values and often nonsignificant results (z = 1.96 ≈ p = .05). Studies with high power (e.g., 80% power corresponds to z ≈ 2.8) require either moderate-to-large effect sizes or very large sample sizes. Inspection of the plot shows that most studies cluster at low z-values, with relatively few studies producing z-values greater than 2.8. Thus, even before modeling the data, the distribution indicates that the literature is dominated by low-powered studies.

The actual z-curve analysis fits a model to the distribution of z-values. Studies with low power (small effect sizes, small sample sizes) are likely to produce low z-values and often z-values that are not significant (z = 1.96 ~ p = .05). Studies that have high power (80% power ~ z = 2.8) have moderate to large effect sizes or really large sample sizes). Inspection of the plot shows most studies have low z-values and few studies have z-values greater than 2.8. Thus, even without modeling the data, we can see that this literature is dominated by studies with low power.

The plot also reveals clear evidence of selective reporting. If results were reported without selection, the distribution of z-values would decline smoothly around the significance threshold. Instead, the mode of the distribution lies just above the significance criterion. The right tail declines gradually, whereas the left side drops off sharply. There are too many results with p ≈ .04 and too few with p ≈ .06. This asymmetry provides direct visual evidence of publication bias, independent of any modeling assumptions.

Z-curve uses the distribution of statistically significant results to estimate the Expected Replication Rate (ERR) and the Expected Discovery Rate (EDR). The ERR estimate is conceptually similar to p-curve–based power estimates but is more robust when studies vary in power. In the present analysis, the estimated ERR of 34% closely matches the p-curve estimate reported by Weingarten et al. (33%) but is substantially higher than Sotola’s earlier z-curve estimate (12.5%). However, ERR estimates assume that studies can be replicated exactly, an assumption that is rarely satisfied in psychological research. Comparisons between ERR estimates and actual replication outcomes typically show lower success rates in practice (Bartos & Schimmack, 2022). Moreover, ERR is an average: approximately half of studies have lower replication probabilities, but we generally do not know which studies these are.

The EDR estimates the proportion of all studies conducted—including unpublished ones—that are expected to yield statistically significant results. In this case, the EDR point estimate is 19%, but there is substantial uncertainty because it must be inferred from the truncated set of significant results. Notably, the confidence interval includes values as low as 5%, which is consistent with a scenario in which social priming effects are absent across studies. Thus, these results replicate Sotola’s conclusion that the available evidence does not demonstrate that any nontrivial proportion of studies produced genuine social priming effects.

Pek et al. (2025) noted that z-curve estimates can be overly optimistic if researchers not only select for statistical significance but also preferentially report larger effect sizes. In their simulations, the EDR was overestimated by approximately 10 percentage points. This criticism, however, weakens rather than strengthens the evidential case for social priming, as an EDR of 9% is even less compatible with robust effects than an EDR of 19%.

The z-curve results also provide clear evidence of heterogeneity in statistical power. Studies selected for significance have higher average power than the full set of studies (ERR = 34% vs. EDR = 18%). Information about heterogeneity is especially evident below the x-axis. Studies with nonsignificant results (z = 0 to 1.95) have estimated average power of only 18–20%. Even studies with significant results and z-values up to 4 have estimated average power ranging from 23% to 56%. To expect an exact replication to succeed with 80% power, a study would need to produce a z-value above 4, yet the plot shows that very few studies reach this level.

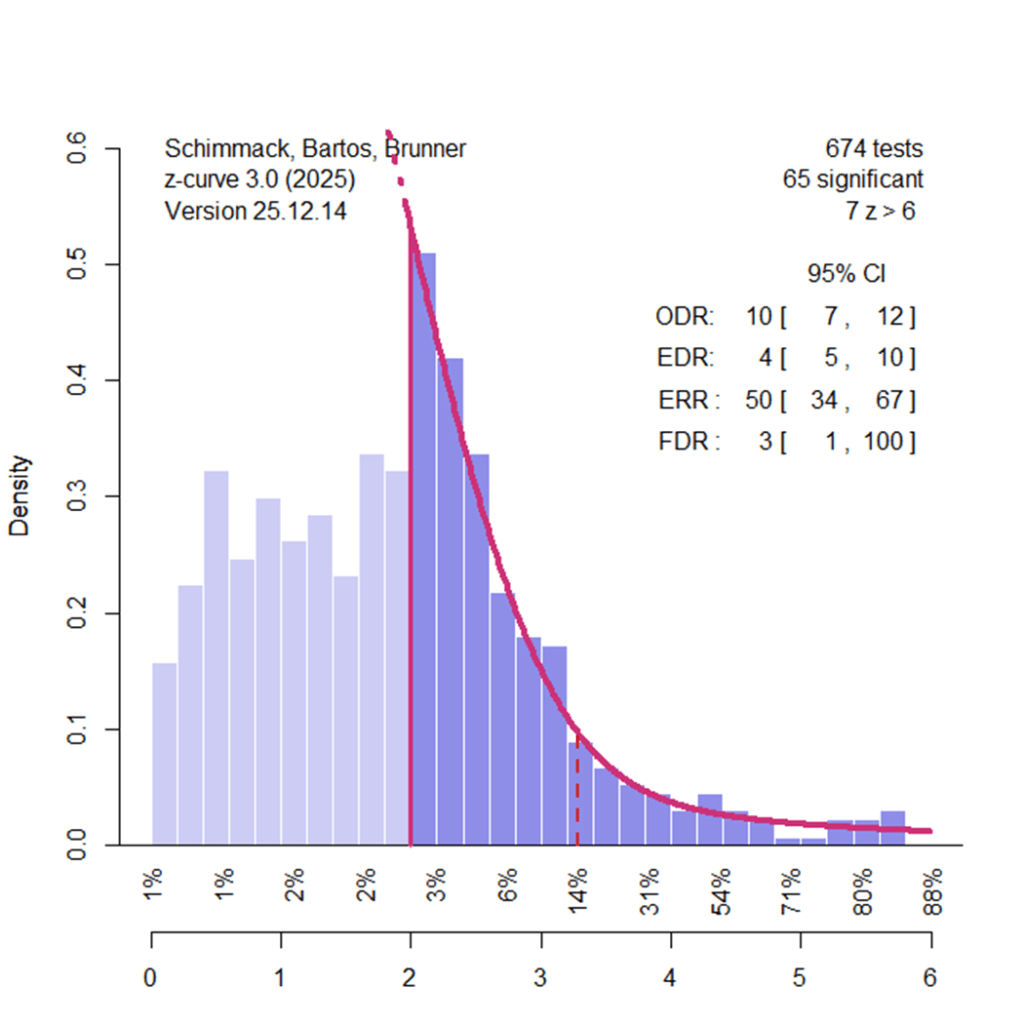

Adjusting Alpha To Lower False Positive Risk

Z-curve can also be used to examine how changing the significance threshold affects false discoveries. With the conventional α = .05 criterion, one out of twenty tests of a true null hypothesis will be significant by chance. Lowering α to .01 reduces this rate to one in one hundred. However, stricter thresholds also reduce power and discovery rates. In some literatures, the reduction in false discoveries outweighs the cost of fewer significant results (Soto & Schimmack, 2024). This is not the case for social priming.

Setting α = .01 (z = 2.58) lowers the point estimate of the false discovery rate from 23% to 11%, but the 95% confidence interval still includes values up to 100%.

Setting α = .001 reduces the point estimate to 3%, yet uncertainty remains so large that all remaining significant results at that threshold could still be false positives.

P-Hacking Real Effects

It is possible to obtain more favorable conclusions about social priming by adopting additional assumptions. One such assumption is that researchers relied primarily on p-hacking rather than selective reporting. Under this scenario, fewer studies would need to be conducted and suppressed. When z-curve is fit under a pure p-hacking assumption, the estimates appear substantially more optimistic.

Under this model, evidence of p-hacking produces an excess of results just below p = .05, which are excluded from estimation. The resulting estimates suggest average power between 40% (EDR = .43) and 52% (ERR = .52), with relatively little heterogeneity. Nonsignificant results with z ≈ 1 are estimated to have average power of 46%, and significant results with z ≈ 4 have average power of 52%. If this model were correct, false positives would be rare and replication should be straightforward, especially with larger samples. The main difficulty with this interpretation is that preregistered replication studies consistently report average effect sizes near zero, directly contradicting these optimistic estimates (Dai et al., 2023).

Conclusion

So, is experimental social psychology a science? The most charitable answer is that it currently resembles a science with limited cumulative results in this domain. Meteorology is not a science because it acknowledges that weather varies; it is a science because it can predict weather with some reliability. Until social priming researchers can specify conditions under which priming effects reliably emerge in preregistered, confirmatory studies, the field lacks the predictive success expected of a mature empirical science.

Meanwhile willful ignorance and incompetence hamper progress towards this goal and undermine credible claims of psychology to be a science. Many psychology departments are being remained to have science in their name, but only acting in accordance with normative rules of science will make psychology a credible science.

Credible sciences also have a history of failures. Making mistakes is part of exploration. Covering them up is not. Meta-analyses of p-hacked studies without bias correction are misleading. Even worse are public significance statements directed at the general public rather than peers. The most honest public significance statement about social priming is “We fucked up. Sorry, we will do better in the future.”

Super interesting!