Wittgenstein might have described science as a kind of language-game: a rule-governed social practice in which the meaning of terms like evidence, effect, replication, and error comes from how they are used and challenged within the activity. On this view, science is not “just talk,” but a distinctive game whose moves are constrained by disciplined observation, measurement, and public criticism, and whose outcomes depend on shared standards for what counts as a good inference.

Consistency is a core rule of the scientific game: theoretical claims should cohere with each other and remain answerable to empirical observations. A major aim of scientific work is to identify tensions—between theory and data, between different datasets, between predictions and replications, or between measurement assumptions and outcomes—and then resolve them by revising theories, improving measurement, or redesigning studies.

In many areas of psychology, however, inconsistency-resolution is weak. Kuhn’s language helps here: psychology is often multi-paradigmatic, with several partially insulated frameworks coexisting, each with its own standards for what counts as a good question, a clean test, and a “successful” result. Under these conditions, contradictions are often routed around rather than confronted—by redefining constructs, adding boundary conditions, switching measures, or shifting statistical conventions. This is reinforced by incentives: researchers are rewarded for producing publishable results within a paradigm, not for cross-paradigmatic work that forces head-to-head adjudication.

The clearest symptom of this weakness is measurement. To study psychological questions, researchers must link variation in unobserved processes (thoughts, feelings, attitudes) to variation in observable scores. But scores are only informative if the mapping from scores to the target construct has been validated. Reliability is not enough. A procedure can produce consistent scores and still fail to measure what it claims to measure. When measures are not validated, inconsistencies proliferate. Instead of treating divergence between measures as a problem to be resolved, psychology often treats each measure as defining its own construct. This operationalist move resolves inconsistency by definition rather than by evidence.

The Implicit Association Test (IAT) is a particularly clear case because it has been promoted as a measurement breakthrough: a “window into the unconscious” (Banaji & Greenwald, 2013). Many researchers trained in this tradition have built careers on the claim that the IAT can measure attitudes and cognitions that are not fully accessible to introspection. The most famous IAT is the race IAT, which is often presented as a measure of implicit racial bias. The test is still promoted by Project Implicit as an educational tool for raising awareness about implicit bias.

Project Implicit is a nonprofit organization with annual revenues in the range of several hundred thousand dollars a year (Project Implicit Inc – Nonprofit Explorer – ProPublica). Revenues include consulting and donations, while the public-facing service is free: visitors complete IATs and receive feedback about their “implicit biases.” In return, Project Implicit obtains a massive dataset that fuels research on implicit bias.

This is precisely where the scientific rule about measurement matters. If the IAT is a “window into the unconscious,” then IAT scores should function as valid measures of a distinct construct—bias that is not accessible to introspection and that therefore cannot be captured by self-report. But strong claims require strong validation. The issue is not whether IAT scores show reliable individual differences. The issue is what those differences mean: do they reflect an unconscious attitude, a general preference that is also accessible to self-report, or task-specific artifacts that are not attitudes at all?

A recent article claims to show that IAT scores are valid measures of racial bias that predicts behavior (e.g., trusting a partner with money) and is distinct from self-reported bias (Axt et al., 2025). The paper mentions a critical perspective, but it does not engage with the central objection raised repeatedly in earlier exchanges: that the same pattern can arise from shared task-specific overlap among similar measures, rather than from uniquely higher validity of the IAT (Bar-Anan & Vianello, 2018; Schimmack, 2020; Vianello & Bar-Anan, 2020).

I view this pattern of citation without uptake—acknowledging criticism while leaving the underlying inference unchanged—as willful incompetence. In this case, repeating the same mistake is not “insanity” (Einstein) because the goal is not to expect a better result. Rather, the goal is to reproduces the same reassuring conclusion and shields core assumptions from potentially fatal criticism.

The mistake is simple: when two measures are very similar, their strong correlation can be mistaken for evidence of higher validity. But similarity can also create shared method variance that inflates correlations and produces spurious evidence of high validity. This is not an exotic technical objection. It is a basic measurement point: two thermometers left in direct sunlight will correlate more strongly with each other than with a thermometer kept in the shade. In that case, sunlight exposure is shared method variance—it makes the instruments agree with each other while distorting the measurement of the construct of interest (temperature).

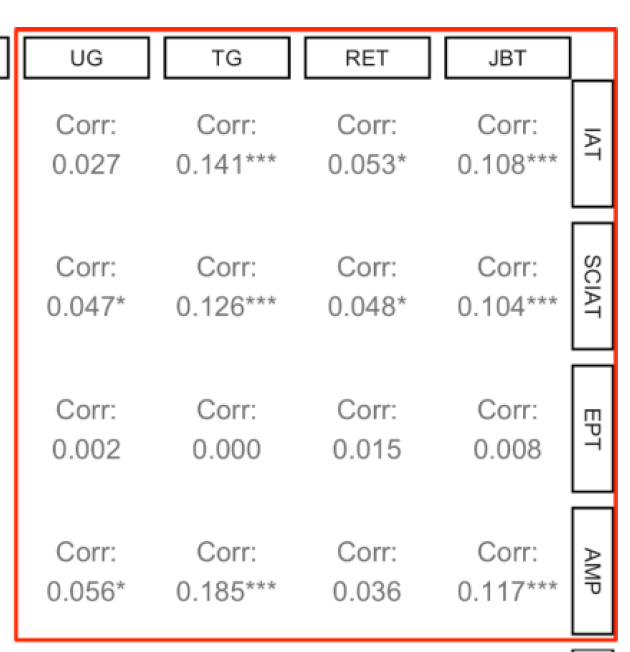

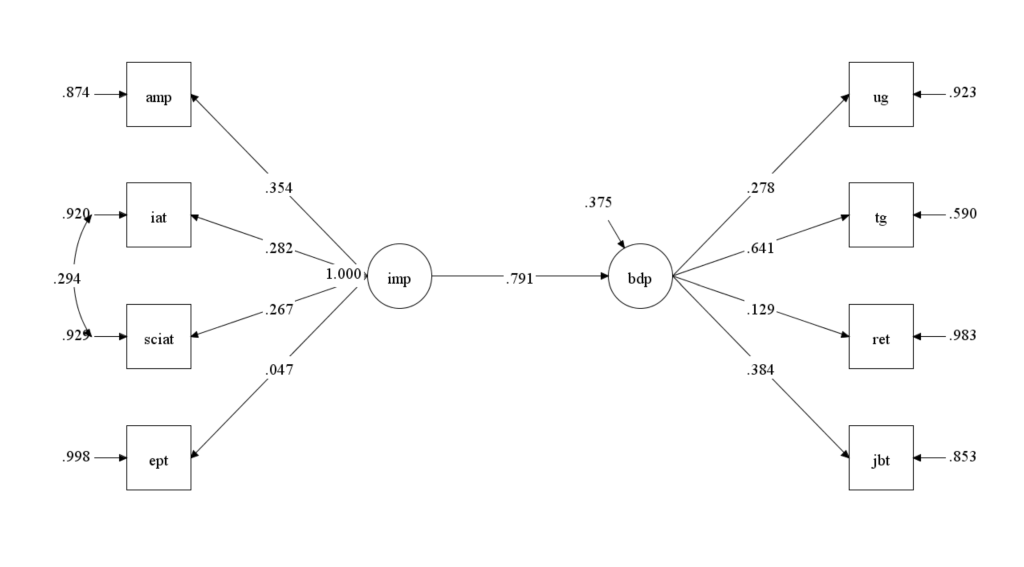

I use the correlation matrix in the 2025 paper to show that shared method variance between two IATs inflated the validity estimates in the published article. First, consider the four implicit tasks that are supposed to measure one common construct— racial bias measured with implicit tasks. Taken at face value, the model suggests that the two IAT measures—the standard race IAT (Black vs. White) and the single-category IAT (Black only)—are “better” measures than the other tasks because their links to the common factor are stronger, while the other tasks show little relationship.

Figure 1. The model shows the influence of a hypothetical common cause on the four implicit tasks. The numbers are validity coefficients. A value of .6 can be interpreted as evidence that there is an ~ 80% probability that somebody above average on the unobserved common cause is also above average on a specific task.

But this interpretation has an obvious alternative explanation: the two IATs are more similar tasks than the other measures, so they may share task-specific influences. From the correlations among the tasks alone, we cannot tell whether the IATs are better measures of racial bias, or whether they mainly share the same kind of measurement noise.

If the IATs are really better measures, they should also be better predictors of biases in the behavioral tasks. But they do not (Figure 2, an exact copy from the article, including the red frame around these correlations). For the race IAT, the correlations with the four behavioral measures are .03, .14, .05, and .11. For the AMP, they are .06, .19, .04, and .12.

The authors discuss the magnitude of these correlations, but they neglect what the pattern implies. The IATs are not better predictors of behavior than the AMP. That pattern is inconsistent with the claim that the IATs are more valid measures of the underlying bias than the AMP, and it suggests that the stronger links for the two IATs in Figure 1 are inflated by shared method variance.

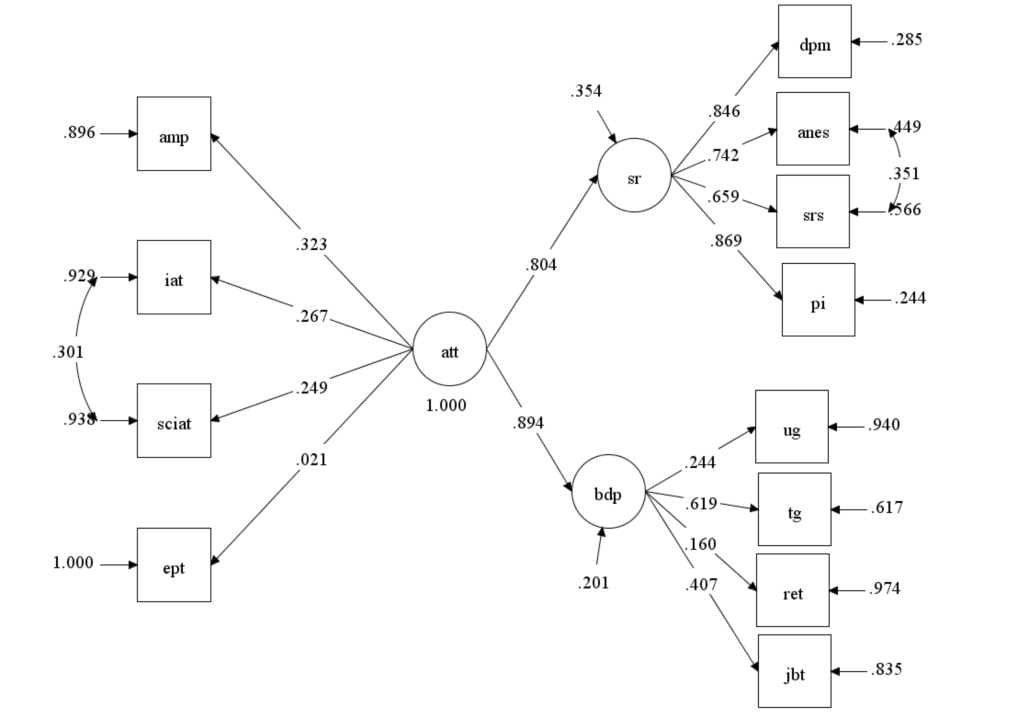

Adding the behavioral tasks to the model makes it possible to separate task-specific overlap from the variance that is actually related to behavior (Figure 3). Consistent with Figure 2, this model shows that the IATs are not more valid than the AMP. A validity of about r = .3 also has a simple practical interpretation. If we treat the underlying bias as the target, an r of .3 implies only modest classification accuracy: roughly 65% of people who are above average in bias would also score above average on the IAT, but about 35% of people who are below average in bias would still score above average on the IAT and receive misleading feedback about their racial bias.

The model in Figure 3 does not tell us, however, whether the implicit tasks measure implicit bias; that is, biases that are outside of people’s awareness. To examine that, we can add self-report measures to the model. When we do, we see that the common factor behind the implicit tasks is strongly related to the self-report factor, r ~ .8 (Figure 4). This means that about 90% of people who are above average in self-reported bias are above average on the “implicit factor,” Clearly, the implicit factor does not represent biases outside of awareness. As Greenwald and Banaji (2017) acknowledged, the IAT is an implicit = indirect measure of bias, not a measure of implicit = unconscious biases; a clarification by the creators of the IAT that is also not cited in this article.

Conclusion

Axt et al.’s (2025) article is a prototypical example of methodological non-response. The authors cite Schimmack (2020), yet the central measurement critique—shared task similarity can inflate correlations and create the appearance of superior validity—is not incorporated into their interpretation. As a result, the paper reproduces reassuring conclusions that make the IAT appear to be a uniquely valid measure of “implicit attitudes” that predict behavior.

It is useful to distinguish two ways paradigms remain insulated from criticism. Willful ignorance is motivational: researchers avoid engaging with threatening evidence, in a way that resembles a Freudian defense mechanism. Willful incompetence, in contrast, can operate as a cognitive blind spot: once certain assumptions are built into a research tradition, they shape the analysis and interpretation of data. Like a visual illusion, the error can persist even when the ingredients for correcting it are present in the data, and outsiders can sometimes see the problem more readily than insiders. In that sense, the case provides an ironic example of “implicit” bias—not necessarily in participants, but in the inferential habits of the research program.

Freud’s specific theory of repression may not be the right model for scientific practice, but the general point stands: strong professional investments can distort how evidence is interpreted. These paradigm-protecting blind spots are reinforced when professional visibility, reputational capital, and institutional missions are tied to sustaining a central claim. What would be the point of Project Implicit if IAT scores were not presented as windows into people’s unconscious?

Brian Nosek, the president of the board and co-founder of Project Implicit was not available for comments, but AI was able to create a plausible response based on interviews and podcasts (1,2).

We appreciate continued scrutiny of how indirect measures like the IAT should be interpreted. It is not surprising that the construct-relevant variance in any single task is modest and that indirect measures show substantial overlap with self-reports—attitudes can be reportable and still operate quickly or automatically in ways people do not fully anticipate or control. On this view, correlations with self-report are not a disconfirmation of “implicit” processes; they reflect that related constructs are being assessed with imperfect tools. We also agree that task similarity and method effects can inflate associations among similar measures, which is precisely why multimethod designs and models that separate shared task overlap from substantive signal are important. The right conclusion is not that indirect measures are meaningless, but that they should be used as part of a broader measurement strategy and interpreted in light of their limitations. Finally, we encourage caution about individual-level interpretation: the IAT is best understood as a research and educational tool that can prompt reflection and guide further inquiry, rather than as a definitive diagnostic of any one person’s “unconscious bias.”

1. https://replicationindex.com/2019/08/17/brain-nosek-explains-the-iat/

2. https://www.charleston-hub.com/podcast/atgthepodcast-287-a-conversation-with-brian-nosek-executive-director-center-for-open-science/

Anthony G. Greenwald developed the IAT. Unfortunately, he was not available for comments. However, AI was able to create a response that aligns with the cautious statements about the validity of IATS in more recent years. (1,2)

Thanks for the thoughtful critique. Let me respond in the spirit of clarity about what the IAT does and does not support.

First, a lot of disagreement here hinges on what we mean by “implicit.” In much of the modern literature, “implicit” is best understood as indirect and/or relatively automatic—not as a strong claim that the relevant evaluations are wholly outside awareness. It’s true that early rhetoric sometimes encouraged the “window into the unconscious” interpretation. But the more defensible position is narrower: the IAT is an indirect behavioral measure of associative/evaluative tendencies that can operate quickly and without deliberate introspection. That is not the same thing as a validated instrument for detecting “unconscious attitudes” in any strong clinical or diagnostic sense.

Second, the point that IAT scores show substantial correlations with self-report does not, by itself, refute the idea that indirect measures can pick up something meaningfully different from questionnaires. Convergence can be a sign that both methods are tracking a common evaluative component. In fact, if the claim is that both implicit tasks and self-reports involve attitudes, it would be surprising if they were unrelated. The more informative question is what the remaining, non-overlapping variance represents. Some of it is surely measurement noise and method-specific variance; some of it may reflect differences in how evaluations are expressed under time pressure, ambiguity, or social desirability constraints. Disentangling those possibilities requires designs that can adjudicate them, not a single correlation.

Third, concerns about shared method variance are real and should be taken seriously. When two tasks are highly similar, they can correlate for task reasons as well as for construct reasons. That is not controversial. But demonstrating method overlap does not automatically imply that the remaining construct-related variance is trivial or that the measure is “invalid.” The right conclusion is conditional: the IAT should not be treated as a uniquely privileged indicator just because it loads strongly in a particular model. Strong loadings can reflect shared task features. That’s precisely why multimethod models, preregistered measurement comparisons, and out-of-sample checks are valuable.

Fourth, there is an important distinction between using the IAT as a research tool and using it as an individual diagnostic. The evidentiary basis is stronger for group-level inference and weaker for high-stakes, person-specific feedback. If people come away thinking the IAT provides a precise readout of their hidden moral character, that’s a misuse. Public-facing feedback should emphasize uncertainty, context sensitivity, and the fact that any single score is noisy and not determinative.

Finally, the strongest version of the criticism—“the valid variance in the IAT is small and largely overlaps with self-report, therefore it does not measure anything meaningfully different”—is an empirical claim that should be tested with sharper predictions. What would count as decisive evidence? For example: preregistered multimethod studies that (a) model method overlap explicitly, (b) use multiple behavior criteria, (c) evaluate incremental prediction in out-of-sample tests, and (d) separate stable trait variance from transient situational variance. If those designs continue to show that the IAT adds little beyond self-report and is mostly method noise, then the appropriate conclusion is modesty about what the IAT can support—not necessarily that the entire enterprise of indirect measurement is meaningless.

In short: I agree with tightening claims. I do not agree that the only scientifically responsible position is to dismiss the IAT wholesale. The more careful position is that the IAT is one imperfect, noisy indicator of evaluative associations—useful in some research contexts, easily overinterpreted in public contexts, and not a warrant for strong claims about unconscious attitudes in individuals.

1 Greenwald and Banaji (2017)

2. Greenwald, Dasgupta, Dovidio, Kang, Moss-Racusin, & Teachman (2022),

Mahzarin R. Banaji also did not comment on the blog post. However, based on recent articles promoting the IAT as a measure of implicit biases, AI was able to create a plausible response that matches her public statements or beliefs (1,2,3).

I appreciate the attention to measurement, but I worry that the critique conflates two different questions: whether the IAT is a perfect indicator of a single latent trait, and whether it is an informative tool for detecting mental associations that can influence judgment and behavior outside of deliberate, reflective endorsement. The IAT was never intended to replace self-report or to treat every millisecond as a pure psychological readout. Its purpose is more modest and more important: to provide a window—imperfect, but informative—into associative evaluations that can operate automatically and sometimes in tension with what people sincerely report about their values.

On the specific psychometric point raised in the blog post, it is entirely reasonable to worry that two highly similar IAT variants will correlate partly because they share task features. Similar tasks share method-related variance; that is true in essentially every area of measurement. But identifying method overlap does not settle the substantive question. At most it shows that strong correlations among IAT-style tasks are not, by themselves, proof of uniquely high construct validity. The appropriate scientific response is to model task similarity explicitly and then evaluate what remains: how strongly the broader indirect-measure factor relates to behavior, and whether that relationship generalizes across outcomes and contexts. That is exactly the kind of measurement refinement that the field should welcome.

The blog post also emphasizes that the common factor behind indirect tasks correlates highly with self-report (e.g., r ≈ .8). It is not clear that this is the reductio it is presented as. A strong relationship with self-report does not imply that the underlying evaluations are fully transparent to introspection, fully endorsed, or fully under conscious control. People can report some attitudes while still underestimating the degree to which automatic associations influence their moment-to-moment judgments, attention, and interpretation of ambiguous events. In other words, overlap between indirect and direct measures is compatible with the existence of implicit processes; it may simply indicate that the same evaluative content is expressed through multiple channels, with different constraints, different opportunities for control, and different vulnerabilities to self-presentation.

At the same time, the blog post is right to insist that we should not treat the IAT as a high-precision individual diagnostic. Most psychological measures are noisy at the individual level, especially when the outcomes of interest are multiply determined. The fact that correlations with behavior are often modest is not a reason to dismiss the phenomenon; it is a reason to be accurate about what level of inference is warranted. In public-facing settings, the IAT is best treated as an educational and research tool that can prompt reflection and motivate attention to situations where bias can matter—not as a definitive label for an individual’s moral character.

Finally, I do not accept the implied dichotomy that either the IAT is a flawless measure or the phenomenon is illusory. The more scientifically responsible middle position is the one reflected in the broader literature: implicit racial bias is a real psychological phenomenon; it can be studied with indirect measures including the IAT; and continued work is needed to refine measurement models, clarify what different components represent, and communicate limitations honestly. If the IAT encourages people to take seriously that their judgments may be influenced by associations they did not choose and do not fully anticipate, then it is doing what it was meant to do.

1. Morehouse, K. N., & Banaji, M. R. (2024). The Science of Implicit Race Bias: Evidence from the Implicit Association Test. Dædalus, 153(1), 21–50. [https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_02047](https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_02047)

2. APA. Speaking of Psychology: Can we unlearn implicit biases? [https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/implicit-biases](https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/implicit-biases)

3. APA. Scientist Spotlight: Mahzarin Banaji. [https://www.apa.org/news/science-spotlight/mahzarin-banaji](https://www.apa.org/news/science-spotlight/mahzarin-banaji)

If you want, I can also “Banaji-ify” a couple of phrases further (more emphasis on automaticity, prediction at scale, and educational purpose) while keeping the scientific engagement.

1. Morehouse, K. N., & Banaji, M. R. (2024). The Science of Implicit Race Bias: Evidence from the Implicit Association Test. Dædalus, 153(1), 21–50. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_02047

2. https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/implicit-biases 3. https://www.apa.org/news/science-spotlight/mahzarin-banaji

Thanks Uli! Great post.

Nobody talks about what are the the key areas for me in understanding what is being measured:

1) If the particular IAT test is based on a stereotype and that stereotype is accurate (Cf Jussim et al.) then are you measuring bias or something else?. E.g. when we put conflicting thoughts in someones head that could be a form of cognitive dissonance.

2) Everybody ignores the lack of slow cultural learning in longitudinal Race IAT. (Cf Dunham et al) Bias does not progress significantly over time in Race IAT despite their efforts to find it in ever younger cohorts.

3) Valence based Gender IAT is swept under the rug or dismissed as an anomaly. Female “implicit ingroup bias” shows BOTH slow cultural learning AND greater than male to female bias. This suggests such anti-male bias is learned behavior. It is also in accord with measures of explicit bias.

4)Contrastingly male to female implicit biases are shown to turn pro female with age in the Project Implicit data. Plausibly correlating with benevolent sexism (aka Chivalry)

These would be good candidates for adversarial collaboration.

1) There are cognitive IATs that assess associations (e.g., Dutch – tall). Here we are assessing how much people associate a group with a trait, and the association can be true or not. The problem with calling any association accurate is that the correlations can be small. Same direction does not make it accurate. The IAT does not quantify how much there is a relationship, so it could be true in direction, without any claims that people know the true strength of the relationship. However, the race IAT is an attitude measure. Do you like White people more than Black people. Most White people do. Would that influence their behavior in interactions with Black and White people. According to the data not much.

2) What do you mean by slow cultural learning? Average IAT scores should only change a lot over time, if actual attitudes change a lot. There is no evidence that this is happening. If the IAT changes more slowly than other measures, it could show that it has a stable (racist) measurement error. There is no support for the claim that explicit attitudes change faster than implicit ones, because there is no evidence that there are implicit attitudes.

3) I don’t know much about the gender IAT.

Comment by Open AI.

First prompt: Review the article.

Second prompt: Read the blog post.

Third prompt: Review the article again.

Final prompt: Write a summary of the review process.

### Commentary

In reviewing the adversarial collaboration by Axt et al. (2025), my original assessment was cautiously supportive. The study’s preregistered, large‑sample SEM analyses suggested that implicit measures—including the race IAT—form a distinct latent construct, reliably detect pro‑White/anti‑Black bias, and add a small but nonzero increment of predictive validity (~2.5%) beyond explicit self‑reports. I emphasized that explicit measures explained far more variance (~45%), but nonetheless saw the implicit factor as statistically separable and modestly informative.

The blog post critique, however, changed my view. It highlights that the stronger loadings of the two IAT variants may be inflated by **shared method variance**, not superior construct validity. Once correlated residuals are modeled, the implicit factor’s distinctiveness weakens, and the IATs no longer outperform the AMP in predicting behavior. Moreover, the blog shows that the “implicit factor” correlates ~.8 with explicit bias, undermining the claim that it measures unconscious attitudes. In practical terms, validity coefficients around r = .3 imply poor classification accuracy, raising concerns about the IAT’s use as a diagnostic tool.

Taken together, the blog post reframes the adversarial collaboration’s reassuring conclusion. Rather than evidence of a uniquely valid measure of unconscious bias, the IAT appears to be an indirect proxy overlapping heavily with explicit attitudes, with its apparent superiority partly driven by task similarity. My assessment therefore shifted from cautious optimism about incremental validity to greater skepticism: the IAT may detect systematic differences, but its distinctiveness and practical utility are far more limited than the published article suggests.

—

Would you like me to **condense this into a 250‑word commentary suitable for a journal response** format, or keep it as a shorter, blog‑style reflection?