In meta-psychology, social priming has become the posterchild of junk science. Researchers conducted many cheap studies with small samples and published the results only when they supported their predictions. After Nobel Laurate Daniel Kahneman published some of these results in his bestselling book “Thinking: Fast and Slow,” he became concerned about the robustness of these results. He send an open letter to the leading social priming research Bargh, asking for replication studies. Bargh and other prominent social priming researchers declined. However, many younger researchers answered the call and reported replication failures. Anybody familiar with the replication crisis in social psychology is well aware of these problems and would not cite social priming studies as scientific evidence unless the studies were preregistered and conducted with reasonable sample sizes to detect small real effects.

However, many psychologists and other social scientists seem to be unaware of the replication crisis or willfully ignore the fact that articles by leading priming researchers provide no credible evidence for the claims made in these articles. As a result, a decade of replication failures has failed to correct the scientific literature. This blog post uses money priming as an example.

The simple idea behind money priming is that some manipulation that makes people think about money will change their attitudes and behaviors in ways that make people more materialistic, selfish, and less altruistic. The original article by Vohs et al. (2006) published 9 studies to provide evidence for this claim. Ironically, an article with 9 successful studies should not make us believe in the effect because even well-designed studies with real effects will occasionally be unsuccessful; that is, produce a p-value above .05 (Schimmack, 2012). Thus, an article that features only successful studies tells us nothing about the actual effect because it is unclear how many attempts were made to get the 9 significant results (Sterling, 1995).

In response to the replication crisis, my colleagues and I have worked on statistical methods to detect selective publishing of confirmatory evidence, which is sometimes called a questionable research practice, but clearly violates the spirit of scientific integrity and undermines the credibility of science and the scientific community. I am focussing on money priming here because I have used Vohs et al.’s (2006) article to train students in bias detection (video). Even 9 studies are sufficient to show that the evidence in this article omits studies that failed to support the mone-priming effect.

I was curious to see whether criticism of priming research and concerns about money priming in general influenced citations of the article. A search in WebOfScience suggests that citations are decreasing. However, citations of psychology articles have been decreasing in 2023 in general and the article is still cited about 20 times a year, which is rather high for psychology. Clearly money priming is not dead yet, and criticizing the work is not akin to flogging a dead horse.

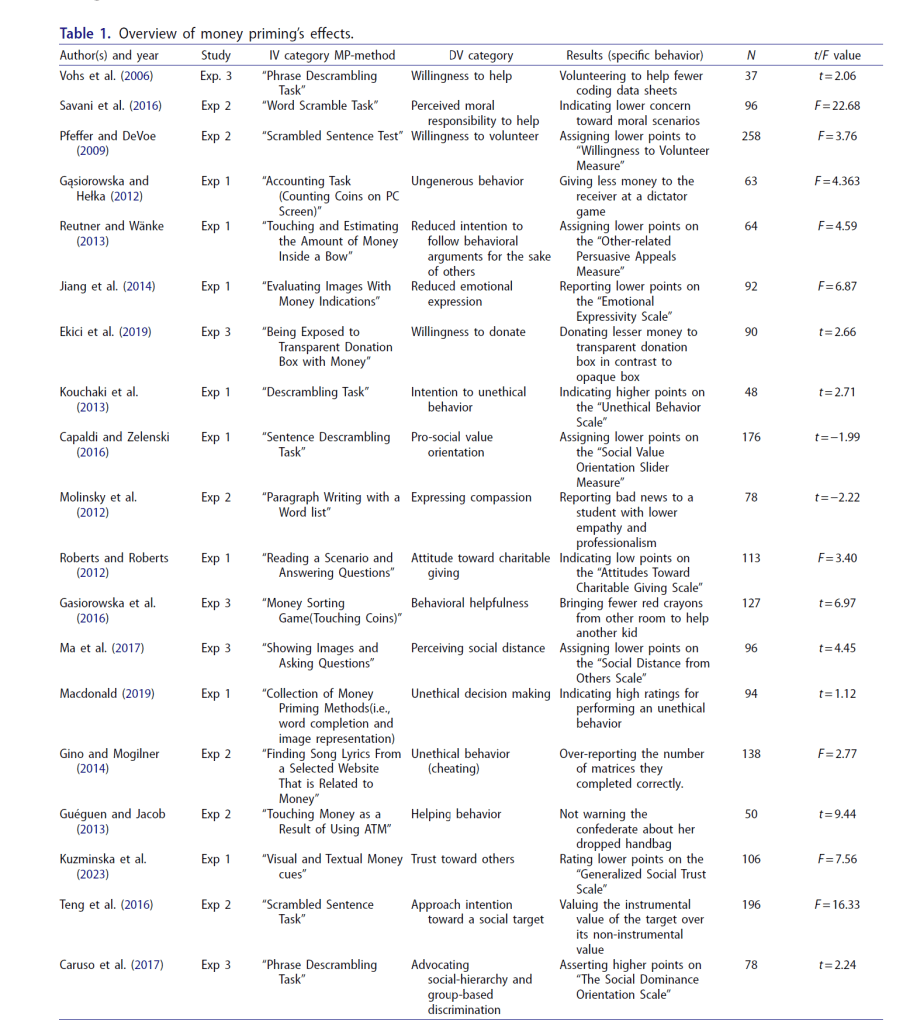

I then looked at articles to see how they cited Vohs et al. (2006). The article “Effects of money priming on sustainable consumption attitudes” caught my attention because the title suggested that it reports results of new money priming research. Indeed, the article reports the results of two successful studies. I will focus on those results a bit later, but first I want to focus on Table 1 in the article that carefully listed results of 19 money priming studies with sample sizes and test statistics (t-tests, F-tests). This is information is sufficient to examine the presence of selection bias in the broader money-priming literature.

I was even able to copy past the table directly into excel. I just needed to add the information about test results in a way that excel could use it and add a few formulas.

The top row shows the important information. 95% of the results were significant if “marginally significant” results (p < .10) are counted as successes. This is consistent with success rates in psychology journals since 1959 (Sterling, 1959). Could this just be due to the fact that money priming is real and that the studies had high statistical power; that is a high probability to get p < .05? The answer to this question can be found by computing the exact p-values for the various test-statistics and converting them into z-scores. These z-scores can be used to compute the observed power of each study based on the effect size estimate in a single study. It is well known that this information is not useful for a single study, but it becomes useful when we have sets of studies and can compute the average power. The average observed power is 66.9%. Thus, we should have gotten about 67% significant results, not 95%. However, observed power is just an estimate of power. Maybe power is really higher? The problem with this argument is that observed power is inflated when selection bias is present. So, the 70% estimate is an overly optimistic estimate and the true average power of the studies is likely to be lower. How much lower? A simpel way to estimate the true average power is to subtract the difference between the success rate and average observed power because the inflation of the estimate increases the more selection bias there is. With an inflation of 94.7% – 67% = 25%, the estimated true power is only 40%. Whether this is sufficient evidence to wonder about the number of studies that failed to show the effect and were not reported is of course a subjective judgment. As the saying goes, a sucker is born every minute.

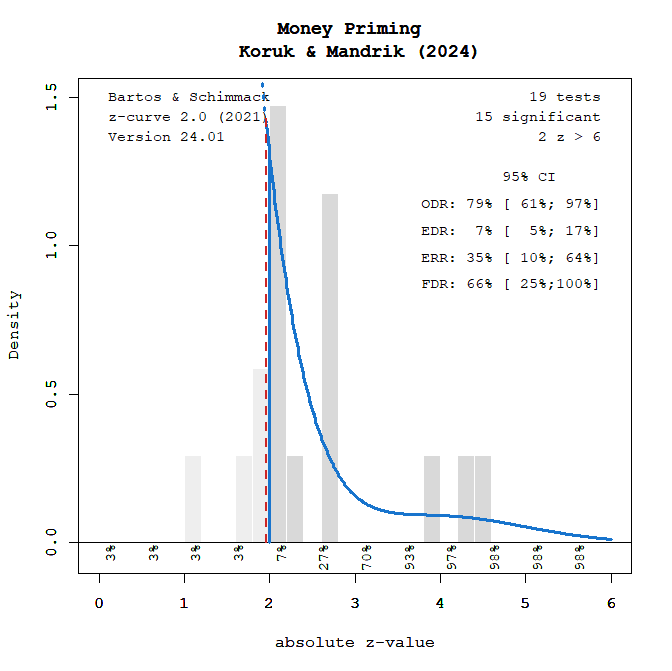

My colleagues and I have developed a more powerful method to examine these kinds of data called z-curve (Bartos & Schimmack, 2022; Brunner & Schimmack, 2021). The method fits a model to the distribution of the z-values implied by test statistics. Visual inspection of the distribution also provides clear evidence that the distribution of z-scores could not have been produced by random sampling error. It is just not possible to get so many results that are just significant (z = 2 implies p = .05) and no non-significant results.

Based on z-curve, we can estimate a number of statistics. The estimated replication rate (ERR) predicts how many of the 95% studies with significant results would produce a significant result again if these studies were repeated exactly with the same sample sizes. It is like asking Bargh to do his study again and show us that he can get the same results again. When asked to do so, he said nobody would believe him anyways if he would report significant results again. The ERR estimate of 35% is less important than the 95% confidence interval around this estimate. The predicted success rate in a set of exact replication studies could be as low as 10%. It could also be as high as 64%, but we just don’t know how replicable these results are. Thus, the 18 (out of 19) significant results tell us practically nothing about the ability to replicate these results.

The other statistic is the expected discovery rate. The expected discovery rate is an estimate of the percentage of significant results that we would find if researchers had kept all of their results and we could find the missing results and see how many significant results we get. The point estimate is very low. We would expect 5% just by chance alone. To get 7% is hardly better than chance. Again, we need to consider the uncertainty in this point estimate. It could be up to 17%, which would imply that researchers get about 1 significant result in 5 attempts (20%). Would you trust a researcher who hides 80% of their results? Moreover, it is also possible that the EDR is 5%, which is chance level. This means that all significant results were obtained by chance alone without any real money priming effect.

To be clear. This is not my data. I didn’t select studies or code studies. The data come from true believers in money priming who used these data to motivate their own studies.

Despite the wealth of adverse effects documented in the literature on money priming in relation to specific behaviors (as outlined in Table 1), there is a noticeable gap in research regarding the impact of money priming on sustainable consumption. (Koruk & Mandrik, 2024, p. 309).

I only plugged the data into stats programs that can look beyond the evidence we see to see whether we can trust the evidence and the answer is that these 19 studies provide no convincing evidence that money priming caused the significant results in these 18 studies. It could just have been chance and selective reporting of significant results.

Now take a moment and predict the outcome of the new studies in this article. Money priming was manipulated with a scrambled sentence task that made participants rearrange words that were either related to money (experimental group) or not (control group) (Exp1) or a paragraph writing task and a picture of money.

The outcome variabel was the average rating to the following three items.

(1) I am concerned about wasting the resources of our planet.

(2) I will make an effort to use products that do not harm the environment.

(3) It is important to change my consumption patterns (use less or avoid buying products) in order to protect the environment

Scroll down to see the results.

Results

Experiment 1 Effect size d = 1.44, z = 9.73

Experiment 2 Effect size d = 1.55, z = 9.18

Let’s just say that these results are very surprising. The effect sizes are very large for results in psychological research in general and the priming literature specifically. A difference of 1.5 standard deviations is as big as the difference in height between men and women.

Due to these large effect sizes, the test-statistic is of the chart. Z-scores of 9 have a probability of 1 out of a gazillion to occur by chance. These are not chance finding. These results are also not consistent with the evidence in Table 1, which showed much lower z-scores for most studies.

There are many possible explanations for these surprising results that include computational errors, demand effects among others (wink). I don’t really care about these results because priming studies are problematic even if they show real effects. First, the manipulation is artificial and may not correspond to real world situations in which we think about money. Second, ratings on a scale do not imply that people would really change their actual behaviors. However, it might still be an easy study to replicate and see whether the results are replicable. Even smaller samples would be sufficient to produce these results again, given the strong effect sizes reported in this article.

The main point of this blog post is that we need to look at results in published articles differently. We cannot just see how many significant results we see in journals. We already know the answer to this question. The published literature tends to have over 90% significant results. This is not an empirical finding that can be used to evaluate evidence. The real question is always how many non-significant are missing. Bias tests can be useful to answer this question. Thus, if you want to be a scientist and make scientific claims you need to examine the amount of bias in the studies that you are using. “Studies show…” is not a scientific claim. Studies also show that extraverts can sense pornography before it is even presented (Bem, 2011). The real question is how many studies really show an effect.