In the 1980s, the five factor model emerged as the dominant model of personality traits. Factors are latent and not directly observable variables. To study these unobserved constructs, personality psychologists developed numerous scales that aim to measure the five factors using item sum scores. These measures differ in length and item content. A prominent measure of the Big Five factors was Costa and McCrae’s Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R). The NEO-PI-R is one of the longest personality surveys with 240 items for two reasons. First, it aims to measure each Big Five factor with six specific traits called facets. Second, the questionnaire needed to have high reliability and validity to be used for assessment of individuals. A modified version of the NEO-PI-R is still being sold for this purpose (Costa & McCrae, 2010).

McCrae et al. (1996) tried to validate the structure of the NEO-PI-R using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). CFA allows researchers to fit a theoretical model to the data to examine whether the model predicts the observed pattern of covariances among observed variables. McCrae et al.’s failed to find satisfactory fit for their theoretical model using CFA. There are reasonable reactions to this outcome (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955). First, researchers may examine whether some of their measures are invalid and need to be revised. Second, researchers may modify their theory to fit the data. However, McCrae et al. did not change their theory or items. Rather, they decided that researches should not use CFA to validate their measures. This response to disconfirming results has been criticized by psychometricians (Borsboom, 2006) and led to criticisms of the Big Five model. Eyeballing a visual plot of the correlations among the 240 items, Cramer et al., (2012) found no support for the five factor model.

As far as I know, there have been no replications of McCrae et al.’s study in nearly 30 years. Here I report the results of one direct and three conceptual replications of McCrae et al.’s study. For ease of comparison, I present the results of the original study and the four replications in one results section.

The original results are based on McCrae et al.’s (1996) principal component analysis of the 30 facet scales (McCrae et al., 1996, Table 4). The parameters cannot be directly compared because principal components are not mathematically equivalent to factors, but loading patterns often tend to be similar. Thus, a close replication should show configural invariance with the same pattern of high and low loadings of facets on big five factors.

The first replication study is based on open data using the NEO-PI-R scale scores of the 30 facets (Goldberg, 2018). This is an exact replication using a new dataset. The second replication used two items for each of the 30 facets to build a measurement model of the 30 facets. The Big Five were modeled as higher-order factors. This is a hierarchical CFA model. The advantage of this approach is that it does not assume validity of facet scores and avoids spurious correlations due to impure scale scores. The other two replications are based on a free, not for profit, questionnaire that aims to measure the 30 facets of the NEO-PI-R (Johnson, 2015). The questionnaire uses 300 items; 10 items for each facet. The dataset is open access and I used only US participants age 20 to 40. The third replication used the scale scores. The fourth replication used a factor model with two items for each of the 30 facets. The complete results (MPLUS outputs) can be found on OSF (https://osf.io/f9q42/).

Model Fit

McCrae et al. (1996) tested various models, but even their most liberal model had a modest Confirmatory Fit Index of .84. The main reason for this poor fit was that they did not allow for correlated residuals. That is, they assumed that unique variance in one facet that is not predicted by the Big Five factors is unrelated to the unique variances of all other facets. They also report that this assumption was violated by the facets activity and achievement striving. The key mistake of McCrae et al.’s attempt was not to allow for such correlated residuals. Is it really implausible that people have to be active to pursue their goals, especially when they are high achievers? McCrae et al. also did not consider the possibility that it is difficult to write items that measure only one facet. Maybe some achievement striving items inadvertently also measured activity level. Analyses based on scale scores cannot rule out this possibility. Only hierarchical analyses with a measurement model of facets can reveal problematic items. To avoid this problem, I selected only items that did not have correlated residuals with other facets. If a correlated residual is only present in analyses of scale scores, it reveals problems with item content. If correlated residuals are also present in hierarchical models, it suggests that Big Five factors do not fully account for the relationship between two facets.

The final model was developed in numerous iterations, until a model with acceptable fit could be found for all four datasets. The final model allowed for free parameters, if a parameter in one of the four models was greater than .2. Thus, the model had equal form (i.e., configural invariance) for all four datasets, but did not constrain the actual loadings. The similarities and differences in the loadings are the key part of the results section.

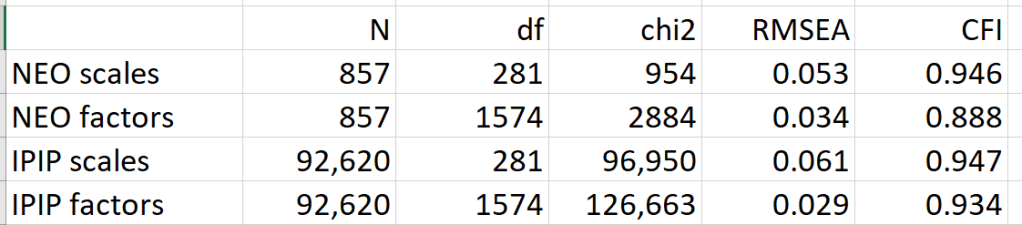

The fit of the final model in the four datasets is reported in Table 1. The modern standards to evaluate model fit are a root mean square error (RMSEA) below .06 and a Comparative Fit Index of .95 or higher. Most models met the RMSEA standard and several models were close to the CFI standard.

Global fit in large models is less important than good fit for individual parameters. Fit of individual parameters was examined using modification indices. For the smaller NEO dataset, MI > 25 were considered as possible parameters. MI < 25 were not considered to avoid overfitting. For the large dataset, MI > 2000 were considered. MI < 2000 often suggested parameters less than .2. Those were not included in the model because they have little practical significance.

The acceptable fit of a single model to four datasets shows that it is possible to fit CFA models to personality data. Thus, McCrae et al.’s dismissal of CFA in a top journal was a mistake that may have impeded development in personality research for decades. Rather than pointing “to serious problems with CFA itself when used to examine personality structure” (McCrae et al., 1996, p. 563), CFA is needed to reveal problems with theories and measures of personality. The following results examine how well McCrae and Costa’s theory fits empirical data.

Primary Loadings

Primary loadings are the highest loadings of a lower order construct (i.e., facet scale or facet factor) on a higher order construct (one of the Big Five factors). Primary loadings should also be strong to provide a good measure of the Big Five. There is no agreed cut-off point for a primary loading. Following McCrae et al. (1996) I used a minimum loading of .4 to confirm that a facet is related to the intended Big Five factor.

The results for Neuroticism replicate the primary loadings of the original study in all four replications except for the facet Immoderation. Immoderation has statistically significant loadings, but they are consistently below .4. Subsequent results of secondary loadings show that Immoderation is more strongly related to low Conscientiousness. This makes Immoderation a poor measure of Neuroticism. The remaining loadings are all high and consistent across NEO and IPIP. Thus, the IPIIP is a viable free alternative to the for-pay NEO scales. In sum, the results replicate the original results, but also show that Immoderation should not be included in a measure of Neuroticism.

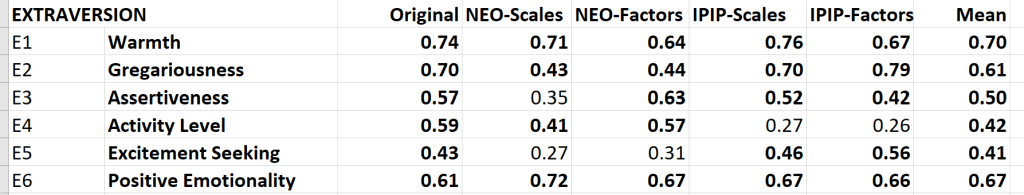

The results for Extraversion replicate the original results in that all average primary loadings are above .4. However, some individual replication studies failed to show the expected loadings. The NEO replications failed to show loadings greater than .4 for Excitement Seeking and the IPIP replications failed to show loadings greater than .4 for Activity Level. These two facets also have average loadings just above .4. Thes results point to problems in the conceptualization and measurement of these facets that might be addressed with better items.

The results for Openness replicate the original results. In fact, the original study showed a low loading for Novelty Seeking (called Adventurousness in the NEO), but all replications showed a loading above .4. However, the loadings for Imagination, Artistic Interests, and Intellectual Curiosity are substantially higher than the loadings of the other facets, suggesting that they are superior for the measurement of this Big Five factor.

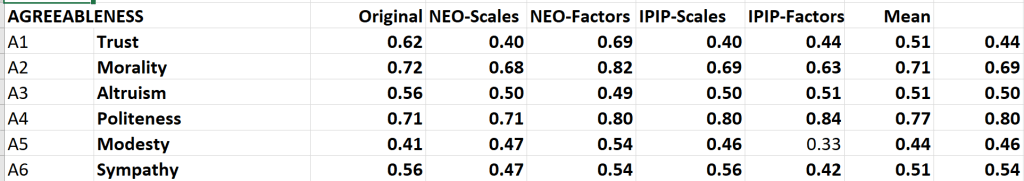

The results for Agreeableness fully replicate the original primary loadings. Morality and Politness consistently show higher loadings than other facets. Modesty has the lowest loading and may not be useful for the measurement of Agreeableness.

The results for Conscientiousness also replicate the original results well.

In sum, the primary loading pattern obtained with principal component analysis by McCrae et al. (1996) replicates in CFA analyses. Thus, there is no justification for the claim that CFA cannot be used to study personality structure. The fact that the primary loading pattern can be obtained using CFA challenges claims that the five factors cannot be found in the 240 NEO-PI-R items (Cramer et al., 2012). Thus, while McCrae et al. were wrong about CFA, their theory of personality remains a viable theory of personality structure.

Secondary Loadings

Principal component analysis and exploratory factor analysis have a lot of freedom to fit data because all observed variables load on all factors without any theoretical rational for these loadings. In CFA, it is common practice to set secondary loadings to zero and assume that an observed variable loads only on one factor. This overly restrictive model often does not fit the data when substantial secondary loadings are present. A solution to this problem is to allow for theoretically justified secondary loadings. For example, Anger is not only related to Neuroticism, but also to low Agreeableness. A model that does not allow for this relationship should not fit the data. Even if no theory predicts secondary loadings, they should be included in a model if they can be replicated. In this case, it is necessary to modify the theory to accommodate a novel finding. Finally, some secondary loadings may be needed to have good model fit, but they are too small to be theoretically important. I focussed on loadings greater than .2 as a minimum to be theoretically interesting. I used Modification Indices and the pattern of secondary loadings in the original study to free parameters for secondary loadings. The following results show how consistent these secondary loadings were across studies.

Table 7 shows all facets that had at least one secondary loading greater than .2 on Neuroticism. The most notable secondary loading was observed for the facet Confidence (NEO Self-Efficacy), L = -.39. For Extraversion facets, Assertiveness had a negative loading, L = -.27. For Openness facets, Emotionality (O3 – Openness to Emotions) had a positive loading, L = .39, and Novelty Seeking had a negative loading, L = -.28. For Agreeableness facets, Trust had a notable negative loading, L = -.33, and Modesty had a notable positive loading, L = .32. All of these secondary loadings replicate secondary loadings above .2 in the original study. Thus, the pattern of secondary loadings is robust across studies and methods and it is misleading to assume that personality has a simple structure. While some facets can be assigned to a specific Big Five factor by means of high (< .4) primary loadings, many also have notable (> .2) secondary loadings on other Big Five factors.

Numerous facets had secondary loadings on Extraversion and most replicated the results of the original study. Some loadings were substantial enough to question the theoretical model underlying the NEO-PI-R. Notably, the Openness facet Emotionality had a strong secondary loading on Extraversion. The only study that did not show this relationship was the IPIP-factor model. This suggests that specific item content creates problems in the measurement of this Openness facet. Trust, Altruism, and Sympathy also show high secondary loadings around .4, showing the difficulty of separating Extraversion and Agreeableness in pro-social behaviors and attitudes. Finally, Extraversion is also negatively related to Impulse Control, a facet of Conscientiousness.

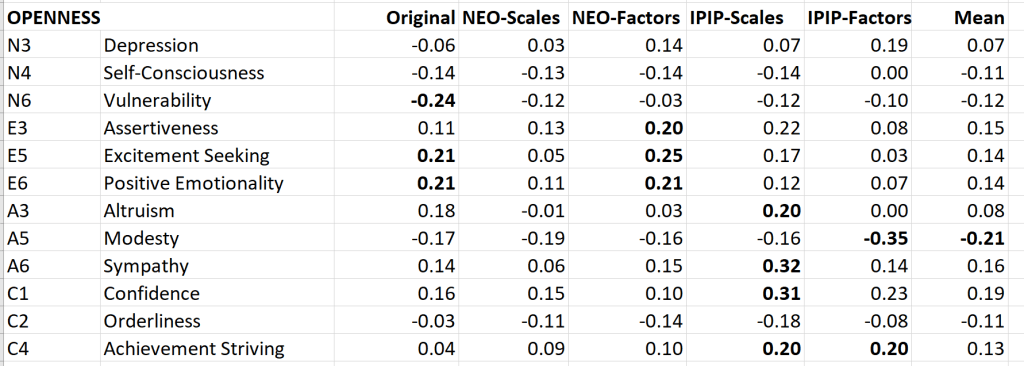

The results for Openness replicate the original results that there are hardly any notable secondary loadings on this Big Five factor.

The results for Agreeableness replicated most of the absolute secondary loadings greater than .2 in the original PCA. The most notable secondary loading is the strong negative loading of Anger on Agreeableness. Anger is best considered a blend of high N and low A, rather than a facet of Neuroticism. The same can be said about Assertiveness that has a strong negative loading on Agreeableness. It is a blend of high E and low A, rather than a facet of Extraversion. Agreeableness is also a strong predictor of low Excitement Seeking, L = -.41, which was already observed in the original study, L = -.39. This robust relationship requires more theoretical discussion. One possible explanation is that Agreeableness may be related to a preference for cooperation (high) versus competition (low) and that competition is a way to seek excitement.

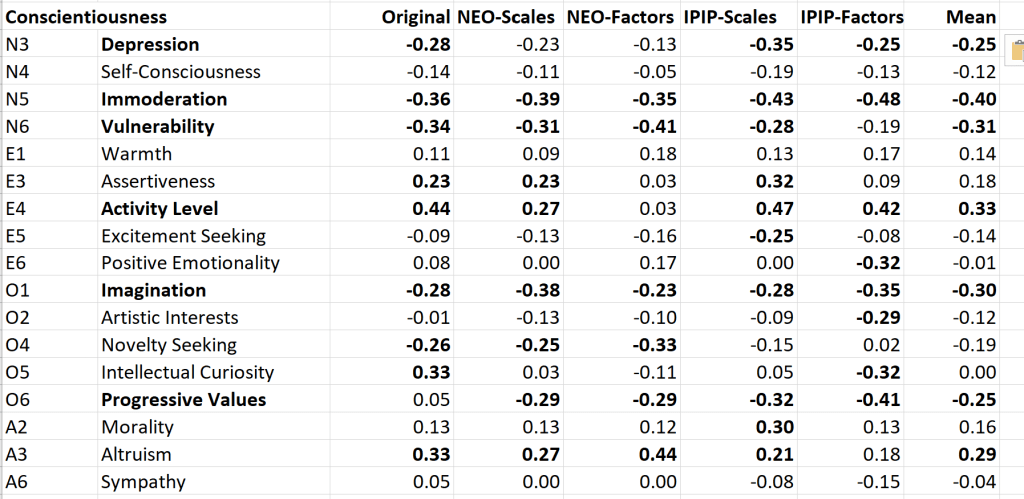

The results for Conscientiousness replicate most of the original results. A notable difference is that the original study showed a positive secondary loading for Intellectual Curiosity that was not replicated. The original study did not show a relationship to Progressive Values, but replication studies showed a negative relationship. L = -.25. The most important result was that the strong negative relationship with Immoderation was replicated. Thus, Immoderation is a complex trait that is related to high N, high E, and low C, and should not be considered a facet of Neuroticism. Activity Level is also strongly related to Conscientiousness. The problem here may be that Extraversion and Conscientiousness are different causes of being active. One is driven by positive energy and the other by determination to achieve long-term goals. More work is needed to see whether these two types of activity can be distinguished.

In conclusion, the pattern of secondary loadings with principal component analysis in the original study is largely replicated with CFA in the replication studies. Thus, simplistic models of a strict hierarchical structure do not fit actual data. While some facets are related primarily to one Big Five factors, others are related to several broader factors. it may be better to describe specific traits by their pattern of relationships with the Big Five than to group them into five discrete domains.

Correlated Residuals

The close replication of primary and secondary loadings suggests that correlated residuals were the cause of low fit in McCrae et al.’s attempt. Correlated residuals continue to be a controversial topic in structural equation modeling (Bandalos, 2021). One concern is that correlated residuals are simply added to achieve model fit without any theoretical rational for the additional relationship. Another concern is that correlated residuals are artifacts that do not replicate across datasets. The following results first examine the replicability of correlated residuals across the four replication studies. Only robust correlated residuals are discussed in terms of their theoretical implications.

The first table shows correlated residuals including a Neuroticism facet. Only 5 correlated residuals had an absolute average of .2 or greater and only one is consistent across the four replications, namely Self-Consciousness and Assertiveness. These results suggest that correlated residuals are mostly method artifacts caused by problems to write items that focus on a single facet. Thus, a logical next step would be to carefully examine the items and to write new items. McCrae et al. (1996) missed this opportunity to improve the validity of the NEO-PI-R by ignoring correlated residuals.

The correlated residual for self-consciousness and assertiveness, however, may require a theoretical explanation. One possible explanation is that self-consciousness makes people less likely to be assertive in social situations. This effect is specific to self-consciousness rather than related to Neuroticism. Thus, the specific focus on social situations may explain why these two facets are correlated. As assertiveness and self-consciousness are only visible in social situations, it is impossible to remove this relationship from items. The presence of this correlated residual does not undermine the Big Five model and there is no need to hide it by using a statistical method that does not allow for correlated residuals like EFA or PCA.

The next table shows the correlated residuals for Extraversion, excluding those with Neuroticism that were already shown in the previous table. There were 9 average correlated residuals with absolute values greater than .2, but only 2 had loadings greater than .2 consistently across the four replications, warmth with gregariousness and activity level with achievement striving. Activity level and achievement striving were also found to be related by McCrae et al. (1996). A plausible explanation is that people high in achievement are more active to pursue their goals. Extraversion may be more related to high levels of energetic arousal (Thayer, 1989). A revision of the items measuring activity level might help to reduce this correlated residual. The correlated residual between warmth and gregariousness may also reveal some problems with item content. Conceptually, Warmth is supposed to measure interest in social contact, whereas gregariousness is limited to specific social contexts like loud parties or events with large groups. It is difficult to be gregarious without also being interested in social context, making it difficult to measure gregariousness without also measuring warmth. Future work might try to find items that measure warmth without contamination of Agreeableness and gregariousness without contamination of warmth.

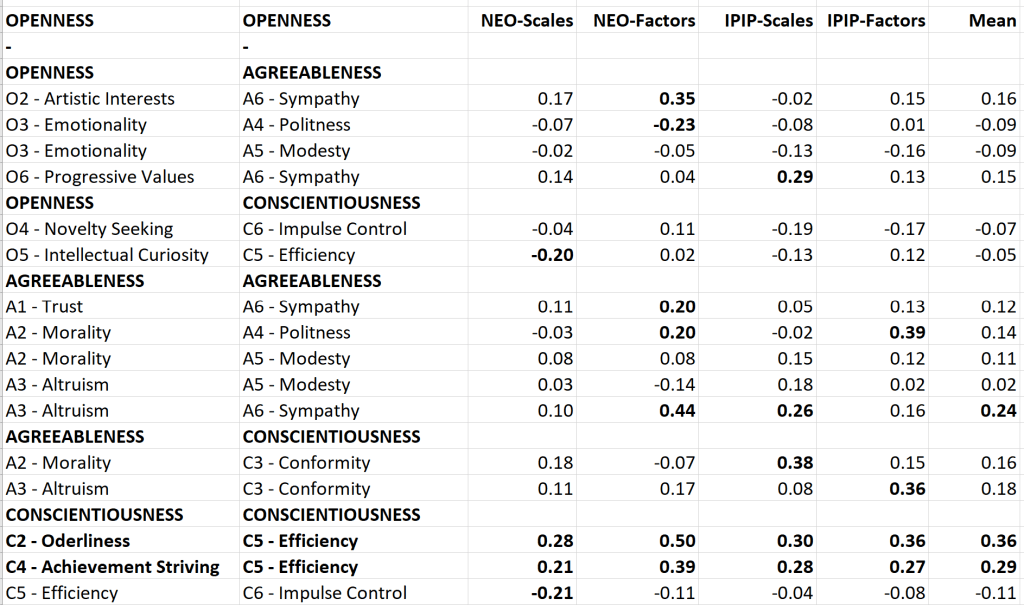

The last table shows the remaining correlated residuals among Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness facets. The most notable correlated residuals were among Conscientiousness facets Orderliness with Efficiency, r = .36, and Achievement Striving and Efficiency, r = .29. There are several explanation for these results that require further investigation. One explanation is that being orderly increases efficiency and that being high in achievement striving also increases efficiency. However, it is also possibel that new items may be able to measure these facets of conscientiousness more discretely.

In conclusion, McCrae et al.’s low fit can be attributed to their reluctance to allow for correlated residuals. The present results show that substantial correlated residuals exist either in one specific datasets and sometimes across datasets. It is rather ridiculous to dismiss CFA because it reveals the presence of these correlated residuals. Inconsistent correlated residuals across replication studies suggest that item content produces correlated residuals. This means that better measures could be developed by testing new items. However, psychologists are often reluctant to revise measures after they have been established. For example, Positive and Negative Affect is measured with a scale developed in 1988, Life Satisfaction is measured with a scale developed in 1985, and self-esteem is measured with a scale developed in 1960. The NEO-PI-R has been revised, but the NEO-PI-3 is not free.

The finding that most of the results with the NEO-PI-R can be replicated with the IPIP items makes it possible to build on Costa and McCrae’s model of personality without using their commercial instruments. The 60-item version of the IPIP can serve as a starting point for further tests of personality structure. With CFA it is easy to test alternative models and to additional items and constructs. Whereas EFA is sensitive to the item pool, this is not the case with CFA. Researchers can fit the hierarchical model to the 60 items and then add additional items and constructs to the model to examien how they relate to the Big Five and specific facets. A 60-item survey also makes it possible to add predictor and outcome variables to the model to extend the nomological network of personality traits.

One limitation of this study, and many other studies of personality, is the reliance on self-reports. Principal component analysis cannot handle multi-rater data. In contrast, CFA makes it easy to address this problem by creating measurement models of facets based on multi-rater data and then testing the same structural model that relates facets to Big Five factors.

In conclusion, McCrae et al.’s article may have impeded progress in personality psychology by dismissing CFA as a tool to study personality structure. The present results show that CFA can be used to examine the replicability of personality structure and provides valuable information that other methods like EFA or principal component analysis do not provide. It is long overdue to correct McCrae et al.’s misleading claims and to encourage a new generation of personality psychologists to subject personality theories to empirical tests that can falsify existing theories to foster theory development. At the same time, the present results show that correlations among the 30 facets of the NEO-PI-R can be modeled with five broad factors. Thus, criticism of the theory based on eyeballing the pattern of correlations among the 240 items can be rejected (Cramer et al., 2012). At present, Costa and McCrae’s hierarchical model of personality remains a viable theory of personality and the present replication studies with CFA provide further support for it.

References

Bandalos, D. L. (2021). Item Meaning and Order as Causes of

Correlated Residuals in Confirmatory Factor Analysis, Structural Equation Modeling: A

Multidisciplinary Journal, 28:6, 903-913, DOI: 10.1080/10705511.2021.1916395

Borsboom, D. (2006). The attack of the psychometricians. Psychometrika, 71(3), 425–440.

Cramer, A. O. J., Van der Sluis, S., Noordhof, A., Wichers, M., Geschwind, N., Aggen, S. H., Kendler, K. S., & Borsboom, D. (2012). Dimensions of normal personality as networks in search of equilibrium: You can’t like parties if you don’t like people. European Journal of Personality, 26(4), 414–431. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1866

Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52(4), 281–302

Goldberg, Lew, 2018, “( 3) NEO-PI-R”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HE6LJR, Harvard Dataverse, V1, UNF:6:Sh2iB6vpAPrVxkaoewIqrg== [fileUNF]

Johnson, J.A. (2015) Johnson’s IPIP-NEO data repository. https://osf.io/tbmh5/